If you’re travelling to Scotland it may be worth learning some of these words. They are heard everywhere, and most of them have been included in the corpus of modern English vocabulary.

←Wauk yer wits

•→wikihow.com/Understand-Scottish-Slang←

↓ Caa canny!

•→Kenneth MacNeill _ Highland clearances ⇐

¤ Scottish Myths & Legends … ⇒[01] ⇔ [02] ⇐

X →St Andrew, Scotland’s patron saint←

…a Scots mocking folk song from the time of the Jacobite Revolution in the 18th century.

Cam ye o’er frae France? Cam ye down by Lunnon? . . . (= London) Saw ye Geordie Whelps and his bonny woman? . . . (= a woman of loose character) Were ye at the place ca’d the Kittle Housie? . . . (= brothel) Saw ye Geordie’s grace riding on a goosie? … (derisive nickname for the King’s mistress) Geordie, he’s a man there is little doubt o’t; He’s done a’ he can, wha can do without it? … (‘blade‘= a person of weak, soft constitution from rapid overgrowth) Down there came a blade linkin’ like my lordie; … (‘linkin’ = tripping along) He wad drive a trade at the loom o’ Geordie. Though the claith were bad, blythly may we niffer; …(‘claith’ = cloth; ‘niffer’ = haggle/exchange) Gin we get a wab, it makes little differ. … (gin = if, whether; wab = web/length of cloth) We hae tint our plaid, bannet, belt and swordie, … (= lost) Ha’s and mailins braid—but we hae a Geordie! … (= houses & farmlands / ‘braid’ = broad) Jocky’s gane to France and Montgomery’s lady; . . . (= gone) There they’ll learn to dance: Madam, are ye ready? They’ll be back belyve belted, brisk and lordly; . . . (= quickly) Brawly may they thrive to dance a jig wi’ Geordie! . . . (= well;) Hey for Sandy Don! Hey for Cockolorum! Hey for Bobbing John and his Highland Quorum! Mony a sword and lance swings at Highland hurdie; . . . (= buttock) How they’ll skip and dance o’er the bum o’ Geordie!¤ ‘The Massacre of Glencoe‘ ⇒

This song recollects a most infamous event in Highland history, when Campbell-led government troops massacred 38 MacDonalds in Glencoe deep in the winter of 1692, after they had accepted their hospitality for two weeks.

On 12 February Glenlyon received written orders from his superior, Major Duncanson:

«You are hereby ordered to fall upon the rebels, the McDonalds of Glencoe, and put all to the sword under seventy. You are to have a special care that the old Fox and his sons do upon no account escape your hands, you are to secure all the avenues that no man escape.»First recorded by Nigel Denver, later by →Alastair McDonald←, thereafter by many others.

· · · John McDermott ⇓

Oh, cruel is the snow that sweeps Glencoe and covers the grave o’ Donald;

Oh, cruel was the foe that raped Glencoe and murdered the house of MacDonald

They came in the blizzard, we offered them heat,

A roof for their heads, dry shoes for their feet;

We wined them and dined them, they ate of our meat,

And they slept in the house of MacDonald

They came from Fort William wi murder in mind;

The Campbell had orders King William had signed;

«Put all to the sword,» these words underlined,

«And leave none alive called MacDonald.»

They came in the night when the men were asleep,

This band of Argyles, through snow soft and deep;

Like murdering foxes amongst helpless sheep,

They slaughtered the house of MacDonald.

Some died in their beds at the hand o the foe;

Some fled in the night and were lost in the snow;

Some lived to accuse him wha struck the first blow,

But gone was the house of MacDonald.

Oh, cruel is the snow that sweeps Glencoe and covers the grave o’ Donald;

Oh, cruel was the foe that raped Glencoe and murdered the house of MacDonald

♦→ The Corries ⇓ The Skye boat song

¤ Music of Scotland ↓ [Wiki Article]

Scotland is internationally known for its traditional music, which has remained vibrant throughout the 20th century, when many traditional forms worldwide lost popularity to pop music. In spite of emigration and a well-developed connection to music imported from the rest of Europe and the United States, the music of Scotland has kept many of its traditional aspects; indeed, it has itself influenced many forms of music.

remained vibrant throughout the 20th century, when many traditional forms worldwide lost popularity to pop music. In spite of emigration and a well-developed connection to music imported from the rest of Europe and the United States, the music of Scotland has kept many of its traditional aspects; indeed, it has itself influenced many forms of music.

Many outsiders associate Scottish folk music almost entirely with the Great Highland Bagpipe, which has indeed long played an important part of Scottish music. Although this particular form of bagpipe developed exclusively in Scotland, it is not the only Scottish bagpipe, and other bagpiping traditions remain across Europe. The earliest mention of bagpipes in Scotland dates to the 15th century although they could have been introduced to Scotland as early as the 6th century. The pìob mhór, or Great Highland Bagpipe, was originally associated with both hereditary piping families and professional pipers to various clan chiefs; later, pipes were adopted for use in other venues, including military marching. Piping clans included the MacArthurs, MacDonalds, McKays and, especially, the MacCrimmon, who were hereditary pipers to the Clan MacLeod.

• Folk music

Folk music takes many forms in a broad musical tradition, although the dividing lines are not rigid, and many artists work across the boundaries. Culturally, there is a split between the Gaelic tradition and the Scots tradition.

The oldest forms of music in Scotland are theorised to be Gaelic singing and harp playing. Although much of the harp tradition was lost through extinction, the harp is being revived by contemporary players. Later, the Great Highland Bagpipe appeared on the scene. The original music of the bagpipe is called Piobaireachd, this is the classical music of the bagpipe. ‘pìobaireachd’ literally means ‘piping’ in Gaelic. It is also known as ‘cèol mòr’ which means ‘great music’. Piobaireachd consists of a theme melody called the ‘ground’ followed by variations. Later, the style of ‘light music,’ including marches, strathspeys, reels, jigs, and hornpipes, became more popular. The British army adopted piping and spread the idea of pipe bands throughout the British Empire. Presently, piping is closely tied to band and individual competitions, although pipers are also experimenting with new possibilities for the instrument. Other forms of bagpipes also exist in the Scottish tradition; they are detailed in the piping section below.

The piping tradition is strongly connected to Gaelic singing (some piping ornaments mimic the Gaelic consonants of the songs), stepdance (the traditional dance meters determine the rhythm of the tunes), and fiddle, which appeared in Scotland in the 17th century. These components are part of the dance music which is played across Scotland at country dances, ceilidhs, Highland balls and frequently at weddings. Group dances are performed to music provided typically by an ensemble, or dance band, which may include fiddle, bagpipe, accordion, tin whistle, cello, keyboard and percussion. Many modern Scottish dance bands are becoming more lively and innovative, with influences from other types of music (most notably jazz chord structures) becoming noticeable.

Vocal music is also popular in the Scottish musical tradition. There are ballads and laments, generally sung by a lone singer with backing, or played on traditional instruments such as harp, fiddle, accordion or bagpipes. There are many traditional folk songs, which are generally melodic, haunting or rousing. These are often very specific to certain regions, and are performed today by a burgeoning variety of folk groups. Popular songs were originally produced by music hall performers such as Harry Lauder and Will Fyffe for the stage. More modern exponents of the style have included Andy Stewart, Glen Daly, Moira Anderson, Kenneth McKellar, Calum Kennedy and the Alexander Brothers.

• Revival

In the 20th century, collections like Last Leaves of Traditional Ballads and Ballad Airs, collected by Reverend James Duncan and Gavin Greig, helped inspire the ensuing folk revival. These were followed by collectors like Hamish Henderson and Calum McLean, both of whom worked with American musicologist Alan Lomax. Earlier, the first Celtic music international star, James Scott Skinner, a fiddler known as the «Strathspey King», had gained fame with some very early recordings.

Among the folk performers discovered by Henderson, McLean and Lomax was Jeannie Robertson, who was brought to sing at the People’s Festival in Edinburgh in 1953. Across the Atlantic, in the United States, pop-folk groups like The Weavers, Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie were leading a folk revival; the singers at the 1951 People’s Festival, John Strachan, Flora MacNeil, Jimmy MacBeath and others, began the Scottish revival.

Like many countries, Scotland underwent a roots revival in the 1960s, although arguably the music was never dead to ‘revive’ it. Folk music had declined somewhat in popularity during the preceding generation, although performers like Jimmy Shand, Kenneth McKellar, and Moira Anderson still maintained an international following and mass market record sales, but numerous young Scots thought themselves separated from their country’s culture. A new wave of Scottish folk performers inspired by American traditionalists like Pete Seeger soon found its own heroes, including young singers Ray and Archie Fisher and Hamish Imlach, and, from the tradition, Jeannie Robertson and Jimmy MacBeath.

Scottish folk singing was revived by artists including Ewan MacColl, who founded one of the first folk clubs in Britain, singers Alex Campbell, Jean Redpath, Hamish Imlach, and Dick Gaughan and groups like The Gaugers, The Corries, The McCalmans and the Ian Campbell Folk Group. Folk clubs boomed, with a strong Irish influence from The Dubliners. With Irish folk bands like The Chieftains finding widespread popularity, 60s Scottish musicians played in pipe bands and Strathspey and Reel Societies. Musicologist Frances Collinson published The Traditional and National Music of Scotland in 1966 to surprising popular acclaim, as part of the burgeoning Scottish folk revival. Still, until the end of the 60s Scottish music was rarely heard in pubs or on the radio, though Irish traditional music was widespread. The Corries had established a fan-base, while the English band Fairport Convention created a British folk rock scene that spread north in the form of JSD Band and Contraband. A more conventional approach was taken by Andy Stewart, Glen Daly and The Alexander Brothers.

• 1970s

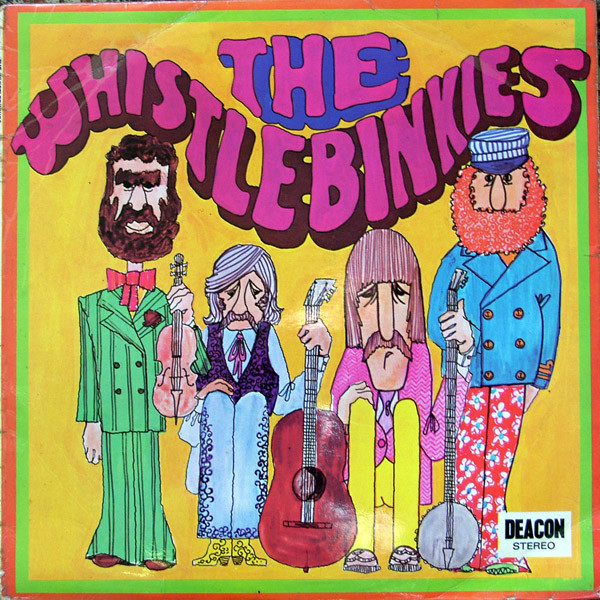

Music had long been primarily a solo affair, until The Clutha, a Glasgow- based group, began solidifying the idea of a Celtic band, which eventually consisted of fiddle or pipes leading the melody, and bouzouki and guitar along with the vocals. Though The Clutha were the first modern band, earlier groups like The Exiles (with Bobby Campbell) had forged in that direction, adding instruments like the fiddle to vocal groups. Alongside The Clutha were other pioneering Glasgow bands, including The Whistlebinkies and Aly Bain’s The Boys of the Lough, both largely instrumental. The Whistlebinkies were notable, along with Alba and The Clutha, for experimenting with different varieties of bagpipes; Alba used Highland pipes, The Whistlebinkies used reconstructed Border pipes and The Clutha used Scottish smallpipes alongside Highlands.

based group, began solidifying the idea of a Celtic band, which eventually consisted of fiddle or pipes leading the melody, and bouzouki and guitar along with the vocals. Though The Clutha were the first modern band, earlier groups like The Exiles (with Bobby Campbell) had forged in that direction, adding instruments like the fiddle to vocal groups. Alongside The Clutha were other pioneering Glasgow bands, including The Whistlebinkies and Aly Bain’s The Boys of the Lough, both largely instrumental. The Whistlebinkies were notable, along with Alba and The Clutha, for experimenting with different varieties of bagpipes; Alba used Highland pipes, The Whistlebinkies used reconstructed Border pipes and The Clutha used Scottish smallpipes alongside Highlands.

Bert Jansch and Davy Graham took blues guitar and eastern influences into their music, and in the mid-1960s, the most popular group of the Scottish folk scene, the Incredible String Band, began their career in Clive’s Incredible Folk Club in Glasgow taking these influences a stage further. The next wave of bands, including Silly Wizard, The Tannahill Weavers, Battlefield Band, Ossian and Alba, featured prominent bagpipers, a trend which climaxed in the 1980s, when Robin Morton‘s A Controversy of Pipers was released to great acclaim. By the end of the 1970s, lyrics in the Scottish Gaelic language were appearing in songs by Na h-Òganaich and Ossian, with Runrig‘s Play Gaelic in 1978 being the first major success for Gaelic-language Scottish folk.

Established Scottish folk club performers such as Archie Fisher, The Corries, Rab Noakes, and Gerry Rafferty in the ‘Humblebums’ with Billy Connolly, introduced more contemporary flavours to a traditional audience by writing and presenting their own new ‘folk’ songs. Robin Williamson, and Mike Heron of The Incredible String Band also created new songs and music in an acoustic style, which while very different, remained sympathetic to traditional Scottish music and took the contemporary sound to a much wider folk crowd. It was the Corries however, who were to take Scottish folk music to its largest audience with a combination of atmospheric arrangements of older folk and new songs which connected the Scotland of the past with Scotland of today.

A growing taste for new songs in the 70s and 80s, sometimes justified as reminiscent of the original roots of folk music, saw some Scottish folk performers move to concentrate entirely on new self penned songs. Established Scots song writers Bennie Gallagher and Graham Lyle, who had a UK hit with McGuinness Flint, performed as a successful duo throughout the 1970s presenting strong new songs which were often covered by mainstream pop artists. Guitarist and songsmith, English born adopted Scot, John Martyn, who started his professional career under the guidance of Hamish Imlach, [ref: Ed: Colin Larkin:The Guinness who’s who of Folk Music], together with Gerry Rafferty, and Gallaher and Lyle inspired a whole new wave of Scots singer songwriters. Dougie MacLean emerged from his roots in traditional bands such as Puddocks Well, and Tannahill Weavers, and carved a successful solo career as a singer songwriter, with his own record label producing some of Scotland’s best known pieces including “The Geal” and “Caledonia”.

Early 80s duo Findask, toured extensively playing self penned original songs in a traditional framework. Their melodies and arrangements were often catchy and complex, while Willie Lindsay’s lyrics, revealed their Glasgow roots, but were appreciated by contemporary reviewers, as witty and literate. Willie Lindsay and Stuart Campbell recorded four albums of original songs throughout the 1980s tackling Scottish issues big and small from “Independence Day” to elated football emotions “Going to Hampden”. [ref:Ed: Colin Larkin: The Guinness who’s who of Folk Music: ]

¤ Instruments

• Accordion

• Accordion

Though often derided as Scottish kitsch, the accordion has long been a part of Scottish music. Country dance bands, such as that led by the renowned Jimmy Shand, have helped to dispel this image. In the early 20th century, the melodeon (a variety of diatonic button accordion) was popular among rural folk, and was part of the bothy band tradition. More recently, performers like Phil Cunningham (of Silly Wizard) and Sandy Brechin have helped popularise the accordion in Scottish music.

• Bagpipes

Though bagpipes are closely associated with Scotland by many outsiders, the instrument (or, more precisely, family of instruments) is found throughout large swathes of Europe, North Africa and South Asia. The most common bagpipe heard in modern Scottish music is the Great Highland Bagpipe, which was spread by the Highland regiments of the British Army. Historically, numerous other bagpipes existed, and many of them have been recreated in the last half-century.

The classical music of the Great Highland Bagpipe is called Pìobaireachd, which consists of a first movement called the urlar (in English, the ‘ground’ movement,) which establishes a theme. The theme is then developed in a series of movements, growing increasingly complex each time. After the urlarthere is usually a number of variations and doublings of the variations. Then comes the taorluathmovement and variation and the crunluath movement, continuing with the underlying theme. This is usually followed by a variation of the crunluath, usually the crunluath a mach (other variations:crunluath breabach and crunluath fosgailte) ; the piece closes with a return to the urlar.

Bagpipe competitions are common in Scotland, for both solo pipers and pipe bands. Competitive solo piping is currently popular among many aspiring pipers, some of whom travel from as far as Australia to attend Scottish competitions. Other pipers have chosen to explore more creative usages of the instrument. Different types of bagpipes have also seen a resurgence since the 70s, as the historical border pipes and Scottish smallpipes have been resuscitated and now attract a thriving alternative piping community.

The pipe band is another common format for highland piping, with top competitive bands including theVictoria Police Pipe Band from Australia (formerly), Northern Ireland‘s Field Marshal Montgomery, Canada’s 78th Fraser Highlanders Pipe Band and Simon Fraser University Pipe Band, and Scottish bands like Shotts and Dykehead Pipe Band and Strathclyde Police Pipe Band. These bands, as well as many others, compete in numerous pipe band competitions, often the World Pipe Band Championships, and sometimes perform in public concerts.

• Fiddle

Scottish traditional fiddling encompasses a number of regional styles, including the bagpipe-inflected west Highlands, the upbeat and lively style of Norse-influenced Shetland Islands and the Strathspey and slow airs of the North-East. The instrument arrived late in the 17th century, and is first mentioned in 1680 in a document from Newbattle Abbey in Midlothian, Lessones For Ye Violin.

including the bagpipe-inflected west Highlands, the upbeat and lively style of Norse-influenced Shetland Islands and the Strathspey and slow airs of the North-East. The instrument arrived late in the 17th century, and is first mentioned in 1680 in a document from Newbattle Abbey in Midlothian, Lessones For Ye Violin.

In the 18th century, Scottish fiddling is said to have reached new heights. Fiddlers like William Marshall and Niel Gow were legends across Scotland, and the first collections of fiddle tunes were published in mid-century. The most famous and useful of these collections was a series published by Nathaniel Gow, one of Niel’s sons, and a fine fiddler and composer in his own right. Classical composers such as Charles McLean, James Oswald and William McGibbon used Scottish fiddling traditions in their Baroque compositions.

Scottish fiddling is the root of much American folk music, such as Appalachian fiddling, but is most directly represented in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, an island on the east coast of Canada, which received some 25,000 emigrants from the Scottish Highlands during the Highland Clearances of 1780–1850. Cape Breton musicians such as Natalie MacMaster, Ashley MacIsaac, and Jerry Holland have brought their music to a worldwide audience, building on the traditions of master fiddlers such as Buddy MacMaster and Winston Scotty Fitzgerald.

Among native Scots, Aly Bain and Alasdair Fraser are two of the most accomplished, following in the footsteps of influential 20th century players such as James Scott Skinner, Hector MacAndrew, Angus Grant and Tom Anderson Iain MacFarlane, Catriona MacDonald, Eilidh Steel, Jenna Reid. The growing number of young professional Scottish fiddlers makes a complete list impossible.

The Annual Scots Fiddle Festival which runs each November showcases the great fiddling tradition and talent in Scotland.

• Guitar

• Guitar

The history of the guitar in traditional music is recent, as is that of the cittern and bouzouki, which in the forms used in Scottish and Irish music only date to the late 1960s. The guitar featured prominently in the folk revival of the early 1960s with the likes of Archie Fisher, the Corries, Hamish Imlach, Robin Hall and Jimmie MacGregor. The virtuoso playing of Bert Jansch was widely influential, and the range of instruments was widened by the Incredible String Band. Notable artists include Tony McManus, Dave MacIsaac, Peerie Willie Johnson and Dick Gaughan. Other notable guitarists in Scottish music scene include Kris Drever of Fine Friday and Lau, and Ross Martin of Cliar, Daimh and Harem Scarem.

• Harp

Material evidence suggests that lyres and/or harp, or clarsach, has a long and ancient history in Scotland, with Iron Age lyres dating from 2300BC. The harp was regarded as the national instrument until it was replaced with the Highland bagpipes in the 15th century. Stone carvings in the East of Scotland support the theory that the harp was present in Pictish Scotland well before the 9th century and may have been the original ancestor of the modern European harp and even formed the basis for Scottish pibroch, the folk bagpipe tradition.

The Clàrsach (Gd.) or Cláirseach (Ga.) is the name given to the wire-strung harp of either Scotland or Ireland. The word begins to appear by the end of the 14th century. Until the end of the Middle Ages it was the most popular musical instrument in Scotland, and harpers were among the most prestigious cultural figures in the courts of Irish/Scottish chieftains and Scottish kings and earls. In both countries, harpers enjoyed special rights and played a crucial part in ceremonial occasions such as coronations and poetic bardic recitals. The Kings of Scotland employed harpers until the end of the Middle Ages, and they feature prominently in royal iconography. Several Clarsach players were noted at the Battle of the Standard (1138), and when Alexander III (died 1286) visited London in 1278, his court minstrels with him, records show payments were made to one Elyas, «King of Scotland’s harper.»

Three medieval Gaelic harps survived into the modern period, two from Scotland (the Queen Mary Harp and the Lamont Harp) and one in Ireland (the Brian Boru harp), although artistic evidence suggests that all three were probably made in the western Highlands.

The playing of this Gaelic harp with wire strings died out in Scotland in the 18th century and in Ireland in the early 19th century. As part of the late 19th century Gaelic revival, the instruments used differed greatly from the old wire-strung harps. The new instruments had gut strings, and their construction and playing style was based on the larger orchestral pedal harp. Nonetheless the name «clàrsach» was and is still used in Scotland today to describe these new instruments. The modern gut-strung clàrsach has thousands of players, both in Scotland and Ireland, as well as North America and elsewhere. The 1931 formation of the Clarsach Society kickstarted the modern harp renaissance. Recent harp players include Savourna Stevenson, Maggie MacInnes, and the band Sileas. Notable events include the Edinburgh International Harp Festival, which recently staged the world record for the largest number of harpists to play at the same time.

One of the oldest tin whistles still in existence is the Tusculum whistle, found with pottery dating to the 14th and 15th centuries; it is currently in the collection of the Museum of Scotland. Today the whistle is a very common instrument in recorded Scottish music. Although few well-known performers choose the tin whistle as their principal instrument, it is quite common for pipers, flute players, and other musicians to play the whistle as well.

φ Scottish Percussion Instruments

Scottish percussion instruments adhere by and large to Celtic musical traditions. Many of these instruments, such as the Bodhrán, originated in Ireland and beyond and found their way to Scotland through cultural exchange. As with percussive instruments from all regions of the earth, Scottish percussion instruments serve rhythmic or melodic purposes. Drums and other instruments figure in various historical purposes, from celebrations of culture and clan to harbingers of battle. In contemporary times, percussive instruments serve a distinctly traditional role.

Bodhrán

A Celtic percussive instrument, the Bodhrán originated in Ireland. This basic drum exhibits structural similarities to a number of basic drums found in African and Asian cultures. The Bodhrán consists of a simple wooden frame with a goatskin, sheepskin or greyhound skin head. Contemporary makers of the instrument use hide from animals such as reindeer, buffalo, elk and deer. Bodhrán makers buried skins for six to eight weeks as a means of preparation. Percussive musicians used a double-headed stick known as a cipín, tipper, or beater to produce sound from the drum.

Other Drums

Two types of drums commonly accompany bagpipe players. Though not unique to Scotland, these percussive instruments figure prominently in traditional Scottish music. The snare drum keeps a marching, military cadence in compliment with bagpipes. A side-hit drum, or a large bass drum strapped to the chest of the player, provides the basic meter for the rhythm and pace of the bagpipes. When used in military parades or other traditional festivities, the bass drum dictates the pace of the walking or marching.

Bones

Bones, another traditionally Irish instrument that found its way into Celtic Scottish traditions, is exactly what it sounds. This percussive, rhythmic instrument accompanies melodic instruments as a musical accoutrement and never comprises a central instrument in an arrangement. Online resource Celtic Musical Instruments likens bones, which consist of either a pair of cow ribs or thick, dry sticks clapped together, to castanets. Players hold both of the bones or sticks in one hand and click them together by snapping the wrist.

Hammer Dulcimer

The hammer dulcimer is a melodic, stringed percussive instrument common to many folk traditions throughout the world. The instrument comprises a trapezoidal piece of wood with pegs bored into it. These pegs hold strings in much the same manner that guitars do. Despite this similarity to stringed instruments, the hammer dulcimer is played with a hammer or mallet, not the hands. Players hit the strings of the dulcimer with a mallet to create the tones.

◊→Scottish Mouth Music ⇐ Dolores Keane & John Faulkner

∇ The Gael ⇓

ALBANNACH – Φ Hooligan’s Holiday ⇓

Δ Mountains of Scotland: Nevis & Glencoe • •→ Part 1 ⇔ Part 2 ⇔ Part 3←•

♦→ Danny Bhoy – Visitor’s Guide to Scotland ⇐

♦ Visit Scotland with Neil Oliver ⇓

¶ 700 years since the battle of Banockburn (24 June 1314) a referendum for Scottish independence has just taken place: after an unprecedented voter turnout of just under 85 percent, 55.3 percent were against independence to 44.7 percent in favor.

The Battle of Bannockburn (Blr Allt a’ Bhonnaich in Scottish Gaelic) was the decisive battle in the First War of Scottish Independence. Edward came to Scotland in the high summer of 1314 with the preliminary aim of relieving Stirling Castle: the real purpose, of course, was to find and destroy the Scottish army in the field, and thus end the war. England sent a a grand feudal army, comprising more than 2,000 horse and 16,000 foot. The precise size relative to the Scottish forces is unclear but estimates range from as much as at least two or three times the size of the army Bruce had been able to gather, to as little as only 50% larger. . . It was chiefly composed of infantry armed with long spears, and divided into three main (infantry) formations, a force of light cavalry, and the camp followers .

There now occurred one of the most memorable episodes in Scottish history. Henry de Bohun, nephew of the Earl of Hereford, was riding ahead of his companions when he caught sight of the Scottish king. De Bohun lowered his lance and began a charge that carried him to lasting fame. King Robert was mounted on a small palfrey and armed only with a battle-axe. He had no armour on. As de Bohun’s great war-horse thundered towards him, he stood his ground, watched with mounting anxiety by his own army. With the Englishman only feet away, Bruce turned aside, stood in his stirrups and hit the knight so hard with his axe that he split his helmet and head in two. This small incident became in a larger sense a symbol of the war itself: the one side heavily armed but lacking agility; the other highly mobile and open to opportunity.

There now occurred one of the most memorable episodes in Scottish history. Henry de Bohun, nephew of the Earl of Hereford, was riding ahead of his companions when he caught sight of the Scottish king. De Bohun lowered his lance and began a charge that carried him to lasting fame. King Robert was mounted on a small palfrey and armed only with a battle-axe. He had no armour on. As de Bohun’s great war-horse thundered towards him, he stood his ground, watched with mounting anxiety by his own army. With the Englishman only feet away, Bruce turned aside, stood in his stirrups and hit the knight so hard with his axe that he split his helmet and head in two. This small incident became in a larger sense a symbol of the war itself: the one side heavily armed but lacking agility; the other highly mobile and open to opportunity.

You made some decent points there. I did a search on the issue and found most people will go along with with your website.

I completely accept your point.I gained knowledge by reading your informative post.Well ellaborated.I have bookmarked your blog.In these days it is difficult to find blogs like this with unique content.

Wohh precisely what I was searching for, thankyou for posting .

I think other site proprietors should take this site as an model, very clean and great user friendly style and design, let alone the content. You’re an expert in this topic!

Simply a smiling visitor here to share the love (:, btw outstanding style .