¤ Director’s Cut: Underworld by Don DeLillo

For the 60th anniversary of the Shot Heard ‘Round the World, read an excerpt from

Pafko at the Wall ↓ the prologue to DeLillo’s American epic.

Another except from Underworld . . .

This seemed to animate him. He leaned across the desk and gazed, is the word, at my wet boots.

«Those are ugly things, aren’t they?»

«Yes they are.»

«Name the parts. Go ahead. We’re not so chi chi here, we’re not so intellectually chic that we can’t test a student face-to-face.»

«Name the parts,» I said. «All right. Laces.»

«Laces. One to each shoe. Proceed.»

I lifted one foot and turned it awkwardly.

«Sole and heel.»

«Yes, go on.»

I set my foot back down and stared at the boot, which seemed about as blank as a closed brown box.

«Proceed, boy.»

«There’s not much to name, is there? A front and a top.»

«A front and a top. You make me want to weep.»

«The rounded part at the front.»

«You’re so eloquent I may have to pause to regain my composure. You’ve named the lace.

What’s the flap under the lace?»

«The tongue.»

«Well?»

«I knew the name. I just didn’t see the thing.»

He made a show of draping himself across the desk, writhing slightly as if in the midst of some dire distress.

«You didn’t see the thing because you don’t know how to look. And you don’t know how to look because you don’t know the names.» ÷

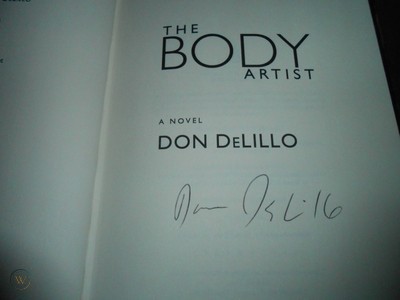

¤ The Body Artist ⇓ [excerpt]

In this spare, seductive novel, DeLillo inhabits the muted world of Lauren Hartke, an artist whose work defies the limits of the body. Lauren is living on a lonely coast in a rambling rented house, where she encounters a strange, ageless man, a man with uncanny knowledge of her own life. Together they begin a journey into the wilderness of time — time, love, and human perception.

… She reached in for the milk, realizing what it was he’d said that she hadn’t heard about eight seconds ago.

Every time she had to bend and reach into the lower and remote parts of the refrigerator she let out a groan, but not really every time, that resembled a life lament. She was too trim and limber to feel the strain and was only echoing Rey, identifyingly, groaning his groan, but in a manner so seamless and deep it was her discomfort too.

Now that he’d remembered what he meant to tell her, he seemed to lose interest. She didn’t have to see his face to know this. It was in the air. It was in the pause that trailed from his remark of eight, ten, twelve seconds ago. Something insignificant. He would take it as a kind of self-diminishment, bringing up a matter so trivial.

She went to the counter and poured soya over the cereal and fruit. The lever sprang or sprung and he got up and took his toast back to the table and then went for the butter and she had to lean away from the counter when he approached, her milk carton poised, so he could open the drawer and get a butter knife.

There were voices on the radio in like Hindi it sounded.

She poured milk into the bowl. He sat down and got up. He went to the fridge and got the orange juice and stood in the middle of the room shaking the carton to float the pulp and make the juice thicker. He never remembered the juice until the toast was done. Then he shook the carton. Then he poured the juice and watched a skim of sizzling foam appear at the top of the glass.

She picked a hair out of her mouth. She stood at the counter looking at it, a short pale strand that wasn’t hers and wasn’t his.

He stood shaking the container. He shook it longer than he had to because he wasn’t paying attention, she thought, and because it was satisfying in some dumb and blameless way, for its own childlike sake, for the bounce and slosh and cardboard orange aroma.

He said, «Do you want some of this?»

She was looking at the hair.

«Tell me because I’m not sure. Do you drink juice?» he said, still shaking the damn thing, two fingers pincered at the spout.

She scraped her upper teeth over her tongue to rid her system of the complicated sense memory of someone else’s hair.

She said, «What? Never drink the stuff. You know that. How long have we been living together?»

«Not long,» he said.

He got a glass, poured the juice and watched the foam appear. Then he wheeled a little achingly into his chair.

«Not long enough for me to notice the details,» he said.

«I always think this isn’t supposed to happen here. I think anywhere but here.»

He said, «What?»

«A hair in my mouth. From someone else’s head.»

He buttered his toast.

«Do you think it only happens in big cities with mixed populations?»

«Anywhere but here.» She held the strand of hair between thumb and index finger, regarding it with mock aversion, or real aversion stretched to artistic limits, her mouth at a palsied slant. «That’s what I think.»

«Maybe you’ve been carrying it since childhood.» He went back to the newspaper. «Did you have a pet dog?»

«Hey. What woke you up?» she said.

It was her newspaper. The telephone was his except when she was calling the weather. They both used the computer but it was spiritually hers.

She stood at the counter looking at the hair. Then she snapped it off her fingers to the floor. She turned to the sink and ran hot water over her hand and then took the cereal bowl to the table. Birds scattered when she moved near the window.

«I’ve seen you drink gallons of juice, tremendous, how can I tell you?» he said.

Her mouth was still twisted from the experience of sharing some food handler’s unknown life or from a reality far stranger and more meandering, the intimate passage of the hair from person to person and somehow mouth to mouth across years and cities and diseases and unclean foods and many baneful body fluids.

«What? I don’t think so,» she said.

Okay, she put the bowl on the table. She went to the stove, got the kettle and filled it from the tap. He changed stations on the radio and said something she missed. She took the kettle back to the stove because this is how you live a life even if you don’t know it and then she scraped her teeth over her tongue again, for emphasis, watching the flame shoot blue from the burner.

She’d had to sort of jackknife away from the counter when he approached to get the butter knife.

She moved toward the table and the birds went cracking off the feeder again. They passed out of the shade beneath the eaves and flew into sunglare and silence and it was an action she only partly saw, elusive and mutely beautiful, the birds so sunstruck they were consumed by light, disembodied, turned into something sheer and fleet and scatter-bright.

She sat down and picked through sections of newspaper and realized she had no spoon. She had no spoon. She looked at him and saw he was sporting a band-aid at the side of his jaw.

She used the old dented kettle instead of the new one she’d just bought because — she didn’t know why. It was an old frame house that had many rooms and working fireplaces and animals in the walls and mildew everywhere, a place they’d rented unseen, a relic of the boom years of the lumbering and shipbuilding trades, way too big, and there were creaking floorboards and a number of bent utensils dating to god knows.

She half fell out of her chair in a gesture of self-ridicule and went to the counter to get a spoon. She took the soya granules back to the table as well. The soya had a smell that didn’t seem to belong to the sandy stuff in the box. It was a faint wheaty stink with feet mixed in. Every time she used the soya she smelled it. She smelled it two or three times.

«Cut yourself again.»

«What?» He put his hand to his jaw, head sunk in the newspaper. «Just a nick.»

She started to read a story in her part of the paper. It was an old newspaper, Sunday’s, from town, because there were no deliveries here.

«That’s lately, I don’t know, maybe you shouldn’t shave first thing. Wake up first. Why shave at all? Let your mustache grow back. Grow a beard.»

«Why shave at all? There must be a reason,» he said. «I want God to see my face.»

He looked up from the paper and laughed in the empty way she didn’t like. She took a bite of cereal and looked at another story. She tended lately to place herself, to insert herself into certain stories in the newspaper. Some kind of daydream variation. She did it and then became aware she was doing it and then sometimes did it again a few minutes later with the same or a different story and then became aware again.

She reached for the soya box without looking up from the paper and poured some granules into the bowl and the radio played traffic and talk.

The idea seemed to be that she’d have to wear out the old kettle, use it and use it until it developed rust bubbles and then and only then would it be okay for her to switch to the kettle she’d just bought.

«Do you have to listen to the radio?»

«No,» she said and read the paper. «What?»

«It is such astonishing shit.»

The way he stressed the t in shit, dignifying the word.

«I didn’t turn on the radio. You turned on the radio,» she said.

He went to the fridge and came back with a large dark fig and turned off the radio.

«Give me some of that,» she said, reading the paper.

«I was not blaming. Who turned it on, who turned it off. Someone’s a little edgy this morning. I’m the one, what do I say, who should be defensive. Not the young woman who eats and sleeps and lives forever.»

«What? Hey, Rey. Shut up.»

He bit off the stem and tossed it toward the sink. Then he split the fig open with his thumbnails and took the spoon out of her hand and licked it off and used it to scoop a measure of claret flesh out of the gaping fig skin. He dropped this stuff on his toast — the flesh, the mash, the pulp — and then spread it with the bottom of the spoon, blood-buttery swirls that popped with seedlife.

«I’m the one to be touchy in the morning. I’m the one to moan. The terror of another ordinary day,» he said slyly. «You don’t know this yet.»

«Give us all a break,» she told him.

She leaned forward, he extended the bread. There were crows in the trees near the house, taking up a raucous call. She took a bite and closed her eyes so she could think about the taste.

He gave back her spoon. Then he turned on the radio and remembered he’d just turned it off and he turned it off again.

She poured granules into the bowl. The smell of the soya was somewhere between body odor, yes, in the lower extremities and some authentic podlife of the earth, deep and seeded. But that didn’t describe it. She read a story in the paper about a child abandoned in some godforsaken. Nothing described it. It was pure smell. It was the thing that smell is, apart from all sources. It was as though and she nearly said something to this effect because it might amuse him but then she let it drop — it was as though some, maybe, medieval scholastic had attempted to classify all known odors and had found something that did not fit into his system and had called it soya, which could easily be part of a lofty Latin term, but no it couldn’t, and she sat thinking of something, she wasn’t sure what, with the spoon an inch from her mouth.

He said, «What?»

«I didn’t say anything.»

She got up to get something. She looked at the kettle and realized that wasn’t it. She knew it would come to her because it always did and then it did. She wanted honey for her tea even though the water wasn’t boiling yet. She had a hyper-preparedness, or haywire, or hair-trigger, and Rey was always saying, or said once, and she carried a voice in her head that was hers and it was dialogue or monologue and she went to the cabinet where she got the honey and the tea bags — a voice that flowed from a story in the paper.

«Weren’t you going to tell me something?»

He said, «What?»

She put a hand on his shoulder and moved past to her side of the table. The birds broke off the feeder in a wing-whir that was all b’s and r’s, the letter b followed by a series of vibrato r’s. But that wasn’t it at all. That wasn’t anything like it.

«You said something. I don’t know. The house.»

«It’s not interesting. Forget it.»

«I don’t want to forget it.»

«It’s not interesting. Let me put it another way. It’s boring.»

«Tell me anyway.»

«It’s too early. It’s an effort. It’s boring.»

«You’re sitting there talking. Tell me,» she said.

She took a bite of cereal and read the paper.

«It’s an effort. It’s like what. It’s like pushing a boulder.»

«You’re sitting there talking.»

«Here,» he said.

«You said the house. Nothing about the house is boring. I like the house.»

«You like everything. You love everything. You’re my happy home. Here,» he said.

He handed her what remained of his toast and she chewed it mingled with cereal and berries. Suddenly she knew what he’d meant to tell her. She heard the crows in large numbers now, clamorous in the trees, probably mobbing a hawk.

«Just tell me. Takes only a second,» she said, knowing absolutely what it was.

She saw him move his hand to his breast pocket and then pause and lower it to the cup. It was his coffee, his cup and his cigarette. How an incident described in the paper seemed to rise out of the inky lines of print and gather her into it. You separate the Sunday sections.

«Just tell me okay. Because I know anyway.»

He said, «What? You insist you will drag this thing out of me. Lucky we don’t normally have breakfast together. Because my mornings.»

«I know anyway. So tell me.»

He was looking at the paper.

«You know. Then fine. I don’t have to tell you.»

He was reading, getting ready to go for his cigarettes.

She said, «The noise.»

He looked at her. He looked. Then he gave her the great smile, the gold teeth in the great olive-dark face. She hadn’t seen this in a while, the amplified smile, Rey emergent, his eyes clear and lit, deep lines etched about his mouth.

«The noises in the walls. Yes. You’ve read my mind.»

«It was one noise. It was one noise,» she said. «And it wasn’t in the walls.»

«One noise. Okay. I haven’t heard it lately. This is what I wanted to say. It’s gone. Finished. End of conversation.»

«True. Except I heard it yesterday, I think.»

«Then it’s not gone. Good. I’m happy for you.»

«It’s an old house. There’s always a noise. But this is different. Not those damn scampering animals we hear at night. Or the house settling. I don’t know,» she said, not wanting to sound concerned. «Like there’s something.»

÷

←Excerpt from White Noise . . . → More excerpts ⇐

First published in 1984, White Noise by Don deLillo explores the emergence of technology, popular culture, and media in the eyes of Jack Gladney, a professor and the chairman of Hitler studies in the College-on-the Hill.

“All plots tend to move deathward,” Jack surprisingly remarks in one of his lectures. Considering his pervading fear of death and dying, this remark was totally unexpected.

=

¤ Cosmopolis . . .

The official US trailer for ‘Cosmopolis’ (David Cronenberg) starring Robert Pattinson (Eric Packer), Samantha Morton (Vija Kinsky) and Jay Baruchel (Shiner). The film follows Eric Packer (Pattinson), a 28 year old multi-billionaire asset manager who deals with extreme circumstances during a single 24 hour period in New York City ↓

Sleep failed him more often now, not once or twice a week but four times, five. What did he do when this happened? He did not take long walks into the scrolling dawn. There was no friend he loved enough to harrow with a call. What was there to say? It was a matter of silences, not words.

He tried to read his way into sleep but only grew more wakeful. He read science and poetry. He liked spare poems sited minutely in white space, ranks of alphabetic strokes burnt into paper. Poems made him conscious of his breathing. A poem bared the moment to things he was not normally prepared to notice. This was the nuance of every poem, at least for him, at night, these long weeks, one breath after another, in the rotating room at the top of the triplex.

He tried to sleep standing up one night, in his meditation cell, but wasn’t nearly adept enough, monk enough to manage this. He bypassed sleep and rounded into counterpoise, a moonless calm in which every force is balanced by another. This was the briefest of easings, a small pause in the stir of restless identities.

There was no answer to the question. He tried sedatives and hypnotics but they made him dependent, sending him inward in tight spirals. Every act he performed was self-haunted and synthetic. The palest thought carried an anxious shadow. What did he do? He did not consult an analyst in a tall leather chair. Freud is finished, Einstein’s next. He was reading the Special Theory tonight, in English and German, but put the book aside, finally, and lay completely still, trying to summon the will to speak the single word that would turn off the lights. Nothing existed around him. There was only the noise in his head, the mind in time.

When he died he would not end. The world would end.

He stood at the window and watched the great day dawn. The view was across bridges, narrows and sounds and out past the boroughs and toothpaste suburbs into measures of landmass and sky that could only be called the deep distance. He didn’t know what he wanted. It was still nighttime down on the river, half night, and ashy vapors wavered above the smokestacks on the far bank. He imagined the whores were all fled from the lamplit corners by now, duck butts shaking, other kinds of archaic business just beginning to stir, produce trucks rolling out of the markets, news trucks out of the loading docks. The bread vans would be crossing the city and a few stray cars out of bedlam weaving down the avenues, speakers pumping heavy sound.

The noblest thing, a bridge across a river, with the sun beginning to roar behind it.

He watched a hundred gulls trail a wobbling scow downriver. They had large strong hearts. He knew this, disproportionate to body size. He’d been interested once and had mastered the teeming details of bird anatomy. Birds have hollow bones. He mastered the steepest matters in half an afternoon.

He didn’t know what he wanted. Then he knew. He wanted to get a haircut.

He stood a while longer, watching a single gull lift and ripple in a furl of air, admiring the bird, thinking into it, trying to know the bird, feeling the sturdy earnest beat of its scavenger’s ravenous heart.

He wore a suit and tie. A suit subdued the camber of his overdeveloped chest. He liked to work out at night, pulling weighted metal sleds, doing curls and bench presses in stoic repetitions that ate away the day’s tumults and compulsions.

He walked through the apartment, forty-eight rooms. He did this when he felt hesitant and depressed, striding past the lap pool, the card parlor, the gymnasium, past the shark tank and screening room. He stopped at the borzoi pen and talked to his dogs. Then he went to the annex, where there were currencies to track and research reports to examine.

The yen rose overnight against expectations.

He went back up to the living quarters, walking slowly now, and paused in every room, absorbing what was there, deeply seeing, retaining every fleck of energy in rays and waves.

The art that hung was mainly color-field and geometric, large canvases that dominated rooms and placed a prayerful hush on the atrium, skylighted, with its high white paintings and trickle fountain. The atrium had the tension and suspense of a towering space that requires pious silence in order to be seen and experienced properly, the mosque of soft footfall and rock doves murmurous in the vaulting.

He liked paintings that his guests did not know how to look at. The white paintings were unknowable to many, knife-applied slabs of mucoid color. The work was all the more dangerous for not being new. There’s no more danger in the new.

He rode to the marble lobby in the elevator that played Satie. His prostate was asymmetrical. He went outside and crossed the avenue, then turned and faced the building where he lived. He felt contiguous with it. It was eighty-nine stories, a prime number, in an undistinguished sheath of hazy bronze glass. They shared an edge or boundary, skyscraper and man. It was nine hundred feet high, the tallest residential tower in the world, a commonplace oblong whose only statement was its size. It had the kind of banality that reveals itself over time as being truly brutal. He liked it for this reason. He liked to stand and look at it when he felt this way. He felt wary, drowsy and insubstantial.

The wind came cutting off the river. He took out his hand organizer and poked a note to himself about the anachronistic quality of the word skyscraper. No recent structure ought to bear this word. It belonged to the olden soul of awe, to the arrowed towers that were a narrative long before he was born.

The hand device itself was an object whose original culture had just about disappeared. He knew he’d have to junk it.

The tower gave him strength and depth. He knew what he wanted, a haircut, but stood a while longer in the soaring noise of the street and studied the mass and scale of the tower. The one virtue of its surface was to skim and bend the river light and mime the tides of open sky. There was an aura of texture and reflection. He scanned its length and felt connected to it, sharing the surface and the environment that came into contact with the surface, from both sides. A surface separates inside from out and belongs no less to one than the other. He’d thought about surfaces in the shower once.

He put on his sunglasses. Then he walked back across the avenue and approached the lines of white limousines. There were ten cars, five in a curbside row in front of the tower, on First Avenue, and five lined up on the cross street, facing west. The cars were identical at a glance. Some may have been a foot or two longer than others depending on details of the stretch work and the particular owner’s requirements.

The drivers smoked and talked on the sidewalk, hatless in dark suits, sharing an alertness that would be evident only in retrospect when their eyes went hot in their heads and they shed their cigarettes and vacated their unstudied stances, having spotted the objects of their regard.

For now they talked, in accented voices, some of them, or first languages, others, and they waited for the investment banker, the land developer, the venture capitalist, for the software entrepreneur, the global overlord of satellite and cable, the discount broker, the beaked media chief, for the exiled head of state of some smashed landscape of famine and war.

In the park across the street there were stylized ironwork arbors and bronze fountains with iridescent pennies scattershot at the bottom. A man in women’s clothing walked seven elegant dogs.

He liked the fact that the cars were indistinguishable from each other. He wanted such a car because he thought it was a platonic replica, weightless for all its size, less an object than an idea. But he knew this wasn’t true. This was something he said for effect and he didn’t believe it for an instant. He believed it for an instant but only just. He wanted the car because it was not only oversized but aggressively and contemptuously so, metastasizingly so, a tremendous mutant thing that stood astride every argument against it.

His chief of security liked the car for its anonymity. Long white limousines had become the most unnoticed vehicles in the city. He was waiting on the sidewalk now, Torval, bald and no-necked, a man whose head seemed removable for maintenance.

«Where?» he said.

«I want a haircut.»

«The president’s in town.»

«We don’t care. We need a haircut. We need to go crosstown.»

«You will hit traffic that speaks in quarter inches.»

«Just so I know. Which president are we talking about?»

«United States. Barriers will be set up,» he said. «Entire streets deleted from the map.»

«Show me my car,» he told the man.

The driver held the door open, ready to jog around the rear of the car and down to his own door, thirty-five feet away. Where the file of white limousines ended, parallel to the entrance of the Japan Society, another line of cars commenced, the town cars, black or indigo, and the drivers waited for members of diplomatic missions, for the delegates, consuls and sunglassed attachés.

Torval sat with the driver up front, where there were dashboard computer screens and a night-vision display on the lower windshield, a product of the infrared camera situated in the grille.

Shiner was waiting inside the car, his chief of technology, small and boy-faced. He did not look at Shiner anymore. He hadn’t looked in three years. Once you’d looked, there was nothing else to know. You’d know his bone marrow in a beaker. He wore his faded shirt and jeans and sat in his masturbatory crouch.

«What have we learned then?»

«Our system’s secure. We’re impenetrable. There’s no rogue program,» Shiner said.

«It would seem, however.»

«Eric, no. We ran every test. Nobody’s overloading the system or manipulating our sites.»

«When did we do all this?»

«Yesterday. At the complex. Our rapid-response team. There’s no vulnerable point of entry. Our insurer did a threat analysis. We’re buffered from attack.»

«Everywhere.»

«Yes.»

«Including the car.»

«Including, absolutely, yes.»

«My car. This car.»

«Eric, yes, please.»

«We’ve been together, you and I, since the little bitty start-up. I want you to tell me that you still have the stamina to do this job. The single-mindedness.»

«This car. Your car.»

«The relentless will. Because I keep hearing about our legend. We’re all young and smart and were raised by wolves. But the phenomenon of reputation is a delicate thing. A person rises on a word and falls on a syllable. I know I’m asking the wrong man.»

«What?»

«Where was the car last night after we ran our tests?»

«I don’t know.»

«Where do all these limos go at night?»

Shiner slumped hopelessly into the depths of this question.

«I know I’m changing the subject. I haven’t been sleeping much. I look at books and drink brandy. But what happens to all the stretch limousines that prowl the throbbing city all day long? Where do they spend the night?»

•→Read another excerpt ← [from Part Two – chapter 4]

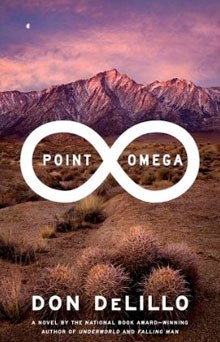

¤ Point Omega ↓ [excerpt]

Unlike “Underworld,” a sprawling, near-epic of a book, “Point Omega”, like most of Don DeLillo’s recent work, is brief, spare and concentrated, a mere 117 pages. There are only three main characters, and their conversations seldom last for more than a couple of sentences. Writing in The New York Times, Michiko Kakutani said that “instead of the jazzy, vernacular, darkly humorous language he employed to such galvanic effect in ‘White Noise’ and ‘Underworld,’ ” Mr. DeLillo had chosen to use “spare, etiolated, almost Beckettian prose.”

Mr. DeLillo got the idea for the book, he said recently, in the summer of 2006, when, wandering through the Museum of Modern Art, he happened upon Douglas Gordon’s “24 Hour Psycho,” a video installation that consists of the Alfred Hitchcock movie “Psycho” slowed down to two frames a second so that it lasts for an entire day instead of the original hour and a half or so […] The slowness of the film, and the way it caused him to notice things he might otherwise have missed, appealed to him, Mr. DeLillo said: “The idea of time and motion and the question of what we see, what we miss when we look at things in a conventional manner — all that seemed very inviting to me to think about.”

Unlike “Underworld,” a sprawling, near-epic of a book, “Point Omega”, like most of Don DeLillo’s recent work, is brief, spare and concentrated, a mere 117 pages. There are only three main characters, and their conversations seldom last for more than a couple of sentences. Writing in The New York Times, Michiko Kakutani said that “instead of the jazzy, vernacular, darkly humorous language he employed to such galvanic effect in ‘White Noise’ and ‘Underworld,’ ” Mr. DeLillo had chosen to use “spare, etiolated, almost Beckettian prose.”

Mr. DeLillo got the idea for the book, he said recently, in the summer of 2006, when, wandering through the Museum of Modern Art, he happened upon Douglas Gordon’s “24 Hour Psycho,” a video installation that consists of the Alfred Hitchcock movie “Psycho” slowed down to two frames a second so that it lasts for an entire day instead of the original hour and a half or so […] The slowness of the film, and the way it caused him to notice things he might otherwise have missed, appealed to him, Mr. DeLillo said: “The idea of time and motion and the question of what we see, what we miss when we look at things in a conventional manner — all that seemed very inviting to me to think about.”

By CHARLES McGRATH [The New York Times – February 3, 2010]

By CHARLES McGRATH [The New York Times – February 3, 2010]

The true life is not reducible to words spoken or written, not by anyone, ever. The true life takes place when we’re alone, thinking, feeling, lost in memory, dreamingly selfaware, the submicroscopic moments. He said this more than once, Elster did, in more than one way. His life happened, he said, when he sat staring at a blank wall, thinking about dinner.

An eight-hundred-page biography is nothing more than dead conjecture, he said.

I almost believed him when he said such things. He said we do this all the time, all of us, we become ourselves beneath the running thoughts and dim images, wondering idly when we’ll die. This is how we live and think whether we know it or not. These are the unsorted thoughts we have looking out the train window, small dull smears of meditative panic.

The sun was burning down. This is what he wanted, to feel the deep heat beating into his body, feel the body itself, reclaim the body from what he called the nausea of News and Traffic.

This was desert, out beyond cities and scattered towns. He was here to eat, sleep and sweat, here to do nothing, sit and think. There was the house and then nothing but distances, not vistas or sweeping sightlines but only distances. He was here, he said, to stop talking. There was no one to talk to but me. He did this sparingly at first and never at sunset. These were not glorious retirement sunsets of stocks and bonds. To Elster sunset was human invention, our perceptual arrangement of light and space into elements of wonder. We looked and wondered. There was a trembling in the air as the unnamed colors and landforms took on definition, a clarity of outline and extent. Maybe it was the age difference between us that made me think he felt something else at last light, a persistent disquiet, uninvented. This would explain the silence.

The house was a sad hybrid. There was a corrugated metal roof above a clapboard exterior with an unfinished stonework path out front and a tacked-on deck jutting from one side. This is where we sat through his hushed hour, a torchlit sky, the closeness of hills barely visible at high white noon.

News and Traffic. Sports and Weather. These were his acid terms for the life he’d left behind, more than two years of living with the tight minds that made the war. It was all background noise, he said, waving a hand. He liked to wave a hand in dismissal. There were the risk assessments and policy papers, the interagency working groups. He was the outsider, a scholar with an approval rating but no experience in government. He sat at a table in a secure conference room with the strategic planners and military analysts. He was there to conceptualize, his word, in quotes, to apply overarching ideas and principles to such matters as troop deployment and counterinsurgency. He was cleared to read classified cables and restricted transcripts, he said, and he listened to the chatter of the resident experts, the metaphysicians in the intelligence agencies, the fantasists in the Pentagon.

The third floor of the E ring at the Pentagon. Bulk and swagger, he said.

He’d exchanged all that for space and time. These were things he seemed to absorb through his pores. There were the distances that enfolded every feature of the landscape and there was the force of geologic time, out there somewhere, the string grids of excavators searching for weathered bone.

I keep seeing the words. Heat, space, stillness, distance. They’ve become visual states of mind. I’m not sure what that means. I keep seeing figures in isolation, I see past physical dimension into the feelings that these words engender, feelings that deepen over time. That’s the other word, time.

I drove and looked. He stayed at the house, sitting on the creaky deck in a band of shade, reading. I hiked into palm washes and up unmarked trails, always water, carrying water everywhere, always a hat, wearing a broad brimmed hat and a neckerchief, and I stood on promontories in punishing sun, stood and looked. The desert was outside my range, it was an alien being, it was science fiction, both saturating and remote, and I had to force myself to believe I was here.

He knew where he was, in his chair, alive to the protoworld, I thought, the seas and reefs of ten million years ago. He closed his eyes, silently divining the nature of later extinctions, grassy plains in picture books for children, a region swarming with happy camels and giant zebras, mastodons, sabertooth tigers.

Extinction was a current theme of his. The landscape inspired themes. Spaciousness and claustrophobia. This would become a theme.

I like this net web-site it’s a master piece! Glad I noticed this on google.

Very interesting details you have observed , thanks for putting up.

I saw a lot of website but I think this one contains something special in it in it