Born on 21 June 1948 in Aldershot, England, he studied at the University of Sussex, where he received a BA degree in English Literature in 1970. He received his MA degree in English Literature at the University of East Anglia.

Sussex, where he received a BA degree in English Literature in 1970. He received his MA degree in English Literature at the University of East Anglia.

McEwan’s works have earned him worldwide critical acclaim. He won the Somerset Maugham Award in 1976 for his first collection of short stories First Love, Last Rites; the Whitbread Novel Award (1987) and the Prix Fémina Etranger (1993) for The Child in Time; and Germany’s Shakespeare Prize in 1999. Amsterdam, described by McEwan as a contemporary fable, was awarded the Booker Prize for Fiction in 1998.

In addition to his prose fiction, Ian McEwan has written plays for television and film screenplays, including The Ploughman’s Lunch (1985), an adaptation of Timothy Mo’s novel Sour Sweet (1988) and an adaptation of his own novel, The Innocent (1993). He also wrote the libretto to Michael Berkeley’s music for the oratorio Or Shall We Die? and is the author of a children’s book, The Daydreamer (1994). Film adaptations of his own novels include First Love, Last Rites (1997), The Cement Garden (1993) and →The Comfort of Strangers (1991), for which Harold Pinter wrote the screenplay, and Atonement (2007).

÷ ÷ ÷

¤ Solar ⇐ [2010]

. . . Ian McEwan reads ‘Solar’ ↓ [from count – 15 min]

[…15 min]

An early sign of Beards distress was dysmorphia, or perhaps it was dysmorphia he was suddenly cured of. At last, he knew himself for what he was. Catching sight of a conical pink mess in the misted full-length mirror as he came out of the shower, he wiped down the glass, stood full on and took a disbelieving look. What engines of self-persuasion had let him think for so many years that looking like this was seductive? That foolish thatch of earlobe-level hair that buttressed his baldness, the new curtain-swag of fat that hung below his armpits, the innocent stupidity of swelling in gut and rear. Once, he had been able to improve on his mirror-self by pinning back his shoulders, standing erect, tightening his abs. Now, human blubber draped his efforts. How could he possibly keep hold of a young woman as beautiful as she was?

Had he honestly thought that status was enough, that his Nobel Prize would keep her in his bed? Naked, he was a disgrace, an idiot, a weakling. Even eight consecutive press-ups were beyond him. Whereas her lover, Tarpin, could run up the stairs to the Beards master bedroom holding under one arm a fifty-kilo cement sack. Fifty kilos? That was roughly Patrice’s weight.

She kept him at a distance with lethal cheerfulness. These were additional insults, her sing-song hellos, the matinal recital of domestic detail and her evening whereabouts, and none of it would have mattered if he had been able to despise her a little and plan to be shot of her. Then they could have settled down to the brief, grisly dismantling of a five-year childless marriage. Of course she was punishing him, but when he suggested that, she shrugged and said that she could just as easily have said the same of him. She had merely been waiting for this opportunity, he said, and she laughed and said in that case she was grateful to him.

In his delusional state he was convinced that just as he was about to lose her he had found the perfect wife. That summer of 2000 she was wearing different clothes, she had a different look around the house faded tight jeans, flip-flops, a ragged pink cardigan over a T-shirt, her blonde hair cut short, her pale eyes a deeper agitated blue. Her build was slight, and now she looked like a teenager. From the empty rope-handled glossy carrier bags and tissue paper left strewn on the kitchen table for his inspection, he gathered she was buying herself new underwear for Tarpin to remove. She was thirty-four, and still kept the strawberries-and-cream look of her twenties. She did not tease or taunt or flirt with him, that at least would have been communication of a sort, but steadily perfected the bright indifference with which she intended to obliterate him . . .

[… 17 min…]

Beard was not wholly sceptical about climate change. It was one in a list of issues, of looming sorrows, that comprised the background to the news, and he read about it, vaguely deplored it and expected governments to meet and take action. And of course he knew that a molecule of carbon dioxide absorbed energy in the infrared range, and that humankind was putting these molecules into the atmosphere in significant quantities. But he himself had other things to think about. And he was unimpressed by some of the wild commentary that suggested the world was in peril, that humankind was drifting towards calamity, when coastal cities would disappear under the waves, crops fail, and hundreds of millions of refugees surge from one country, one continent, to another, driven by drought, floods, famine, tempests, unceasing wars for diminishing resources. There was an Old Testament ring to the forewarnings, an air of plague-of-boils and deluge-of-frogs, that suggested a deep and constant inclination, enacted over the centuries, to believe that one was always living at the end of days, that ones own demise was urgently bound up with the end of the world, and therefore made more sense, or was just a little less irrelevant. The end of the world was never pitched in the present, where it could be seen for the fantasy it was, but just around the corner, and when it did not happen, a new issue, a new date would soon emerge. The old world purified by incendiary violence, washed clean by the blood of the unsaved, that was how it had been for Christian millennial sects death to the unbelievers! And for Soviet Communists death to the kulaks! And for Nazis and their thousand-year fantasy death to the Jews! And then the truly democratic contemporary equivalent, an all-out nuclear war death to everyone! When that did not happen, and after the Soviet empire had been devoured by its own internal contradictions, and in the absence of any other overwhelming concern beyond boring, intransigent global poverty, the apocalyptic tendency had conjured yet another beast.

But Beard was always on the lookout for an official role with a stipend attached. A couple of long-running sinecures had recently come to an end, and his university salary, lecture fees and media appearances were never quite sufficient. Fortunately, by the end of the century, the Blair government wished to be, or appear to be, practically rather than merely rhetorically engaged with climate change and announced a number of initiatives, one of which was the Centre, a facility for basic research in need of a mortal at its head sprinkled with Stockholm’s magic dust. At the political level, a new minister had been appointed, an ambitious Mancunian with a populists touch, proud of his city’s industrial past, who told a press conference that he would tap the genius of the British people by inviting them to submit their own clean-energy ideas and drawings. In front of the cameras he promised that every submission would be answered. Braby’s team half a dozen underpaid post-doctoral physicists housed in four temporary cabins in a sea of mud received hundreds of proposals within six weeks. Most were from lonely types working out of garden sheds, a few from start-up companies with zippy logos and patents pending. . .

With wine and water they raised a toast to magical thinking, then they continued a conversation they had been having by email for some months. To an eavesdropper it would have sounded like the essence of commercial tedium, but to the two men it was a matter of urgency. How many orders for panels were necessary to bring the unit cost down to the point at which they could feasibly claim that a mediumsized artificial-photosynthesis plant could generate electricity as cheaply as coal? The energy market was highly conservative. There was no premium for being virtuous, for not screwing up the climate system. Orders for seven thousand panels, this was their best calculation. Much would depend on whether they could reliably power Lordsburg and its environs night and day for a year, through all kinds of weather. And it also depended on the Chinese, how fast they could move, and how plausibly they could be threatened by the prospect of losing the business. In that respect, the recession helped, but it would also depress demand for panels, if not for energy. They went round this topic a few times, quoting figures, plucking others from the air, then Hammer leaned forward and said confidentially, as though the sole waiter on the far side of the restaurant might hear him, But, Chief, you can be straight with me. Tell me. Is it true, the planet’s getting cooler?

What?

You keep telling me the arguments are over, but they’re not. I’m hearing it everywhere. Last week some woman professor of atmosphere studies or something was saying so on public television.

Whoever she says she is, she’s wrong.

And I’m hearing it everywhere from business people. It seems like its building. They’re saying the scientists have gotten it wrong but don’t dare to admit it. Too many careers and reputations on the line.

What’s their evidence?

They’re saying a point-seven-degree rise since pre-industrial times, thats two hundred and fifty years, is negligible, well within usual fluctuations. And the last ten years have been below the average. We’ve had some bad winters here that doesn’t help our cause. And they’re also saying that too many people are going to get rich on the Obama handouts and tax breaks to want to tell the truth. Then there are all these scientists, including the one I was talking about, who’ve signed up to the Senate Minority Report on Climate Change you must have seen that stuff.

Beard hesitated, then called for more wine. That was the trouble with some of these Californian reds, they were so smoothly accessible, they went down like lemonade. But they were sixteen per cent alcohol. He could not help feeling that this conversation was beneath him. It wearied him, like talking about or against religion, or crop circles and UFOs for that matter. He said, Its zero point eight now, it’s not negligible in climate terms, and most of it has happened in the last thirty years. And ten years is not enough to establish a trend. You need at least twenty-five. Some years are hotter, some are cooler than the year before, and if you drew a graph of average yearly temperatures it would be a zigzag, but a rising zigzag. When you take an exceptionally hot year as your starting point, you can easily show a decline, at least for a few years. Thats an old trick, called framing, or cherry-picking. As for these scientists who signed some contrarian document, they’re in a minority of a thousand to one, Toby. Ornithologists, epidemiologists, oceanographers and glaciologists, salmon fishermen and ski-lift operators, the consensus is overwhelming. Some weak-brained journalists write against it because they think its a sign of independent thinking. And theres plenty of attention out there for a professor who’ll speak against it. There are bad scientists, just like there are rotten singers and terrible cooks.

Hammer looked sceptical. If the place isn’t hotting up, were fucked.

As he refilled his glass, Beard thought how strange it was, that after being associates for all these years, they had rarely discussed the larger issue. They had always concentrated on the business, the matter in hand. Beard also noticed that he himself was close to being drunk.

Here’s the good news. The UN estimates that already a third of a million people a year are dying from climate change. Bangladesh is going down because the oceans are warming and expanding and rising. There’s drought in the Amazonian rainforest. Methane is pouring out of the Siberian permafrost. There’s a meltdown under the Greenland ice sheet that no one really wants to talk about. Amateur yachtsmen have been sailing the North-West Passage. Two years ago we lost forty per cent of the Arctic summer ice. Now the eastern Antarctic is going. The future has arrived, Toby.

Yeah, Hammer said. I guess.

You’re not convinced. Heres the worst case. Suppose the near impossible the thousand are wrong and the one is right, the data are all skewed, there’s no warming. It’s a mass delusion among scientists, or a plot. Then we still have the old stand-bys. Energy security, air pollution, peak oil.

No one’s going to buy a fancy panel from us just because the oils going to run out in thirty years.

What’s wrong with you? Trouble at home?

Nothing like that. Just that I put in all this work, then guys in white coats come on TV to say the planets not heating. I get spooked.

Beard laid a hand on his friends arm, a sure sign that he was well over his limit. Toby, listen. It’s a catastrophe. Relax!

∇ Ian McEwan reads excerpt and is interviewed by Ian Brown at the 2010 Open House Festival in Toronto. ⇓

He got into the suit — it must have weighed twenty pounds — put on the dusty balaclava, squeezed his head into the helmet, put on the inner and outer gloves, then realized that he would not be able to put on the goggles while wearing the gloves, took off the gloves, clamped on the goggles, put on the inner and outer gloves, then remembered that his own ski goggles and gloves, hip flask and stick of lip salve on the seat next to him, would need to be stowed. He took off the inner and outer gloves, put his stuff in a pocket inside his jacket after much struggling with the zip of the outer suit, put on the inner and outer gloves again, and found that in the damp warm air of the lobby and with his own impatient perspiring, his goggles were fogging up. Hot and tired, an unpleasant combination, he stood suddenly in exasperation, turned, and collided with a beam or a column, he couldn’t see which, with a massive cracking sound. How fortunate it was that the Nobel laureate was wearing a helmet. No damage to his skull, but there was now a diagonal crack across the left eyepiece of his goggles, an almost straight line that refracted and diffused the low yellow light in the lobby. To remove the helmet, balaclava, and goggles and wipe the condensation from them he had to remove all four gloves, and now that his hands were sweating, these items were not so easy to dislodge. Once the goggles were off, it was straightforward enough to take them to the almost-cleared breakfast table and employ a crumpled paper napkin, used, but not much used, to polish the lens. Perhaps it was butter, perhaps it was porridge or marmalade that smeared the already scratched plastic, but at least the condensation was off, and it was relatively simple, after replacing the balaclava, to secure the goggles around the helmet and lower it over his head and put on all four gloves and stand, ready at last to face the elements.

His vision was much restricted by the new breakfast coating; otherwise he would have seen the boots earlier lying on their sides under his chair. Off with the gloves — he was not going to lose his temper — and then, after some fiddling with the laces, he decided he would see better without the goggles. Clear sight confirmed that the boots were far too small, by at least three sizes, and there was some relief in knowing that not all the incompetence was his own. But he was game, and thought he would give it one last try, and that was how Jan, entering the lobby with a blast of icy air, found him, trying to push his foot in its hiking boot into a fur-lined snow shoe.

Φ →www.theguardian.com/2012/scienceofclimatechange-ianmcewan ⇐

⇑ [Listen . . . at the count of 17′]

He hurried across baggage reclaim, past the creaking carousels and bored crowds beneath the information screens, through deserted customs, past the sinister one-way glass and the stainless-steel examination tables like bare mortuary slabs, then out along the lines of dead-eyed drivers and their boards – Kuwait Balloon Adventures, Bishop Dolan, Ted of Mr Kipling – and crossed the departure hall, fully aware that he was not quite making a direct line to the stairs that led down to his train, nor was he quite aiming for the down-at-heel airport shop that sold newspapers, luggage straps and related clutter. Was he going to be weak and go in there as he always did? He thought not. But his route was bending that way. He was a public intellectual of a sort, he needed to be informed, and it was natural that he should buy a newspaper, however pressed for time. At moments of important decision-making, the mind could be considered as a parliament, a debating chamber. Different factions contended, short- and long-term interests were entrenched in mutual loathing. Not only were motions tabled and opposed, certain proposals were aired in order to mask others. Sessions could be devious as well as stormy.

He knew this shop too well, and it seemed he was walking directly towards it now. He was simply going in to take a look, test his will, buy a newspaper and nothing besides. If only it were pornography that he was trying to resist, then failure could do him no harm. But pictures of girls or parts of girls no longer stirred him much. His problem was even more banal than top-rack glossies. Now he was at the counter, sorting the pound coins from euros in his hand, with four newspapers under his arm, not one, as if excess in one endeavour might immunise him in another, and as he handed them across for their bar codes to be scanned, he saw at the edge of vision, in the array beneath the till, the gleam of the thing he wanted, the thing he did not want to want, a dozen of them in a line, and without deciding to he was taking one – so light! – and adding it to his pile, partly obliterating a picture of the prime minister waving from the doorway of a church.

It was a plastic foil bag of finely sliced potatoes boiled in oil and dusted in salt, industrialised powdered foodstuffs, preservatives, enhancers, hydrolysing and raising agents, acidity regulators and colouring. Salt and vinegar flavoured crisps. He was still stuffed from his lunch, but this particular chemical feast could not be found in Paris, Berlin or Tokyo and he longed for it now, the actinic sting of these thirty grams – a drug dealer’s measure. One last jolt to the system, then he would never touch the junk again. He thought there was every chance of resisting it until he was on the Paddington train. He stuffed the bag in the pocket of his jacket, took up his burden of papers and his wheeled luggage and continued across the concourse. He was thirty-five pounds overweight. About his future lightness he had made many general resolutions and virtuous promises, often after dinner with a glass in his hand, and all parliamentary heads nodding in assent. What defeated him was always the present, the moment of vivid confrontation with the affirming tidbit, the extra course, the meal he did not really need, when the short-term faction carried the day.

The flight from Berlin was a typical failure. At the start, as he lowered his broad rear into his seat, barely two hours after a meaty Germanic breakfast, he was forming his resolutions: no drinks but water, no snacks, a green-leaf salad, a portion of fish, no pudding, and at the same time, at the approach of a silver tray and the murmured invitation of a female voice, his hand was closing round the stem of his runway champagne. A half-hour later he was ripping open the sachet of a salt-studded, beef-glazed, toasted corn-type sticklet snack that came with his jumbo gin and tonic. Then there was spread before him a white tablecloth, the sight of which fired some neuronal starter gun for his stomach juices. The gin melted his remaining resolve. He chose the starter he had decided against: quails’ legs wrapped in bacon on a bed of creamed garlic. Then, cubes of pork belly mounted on a hill-fort of buttered rice. The word ‘pavé’ was another of those starter guns: a paving slab of chocolate sponge encased in chocolate under a chocolate sauce; goat’s cheese, cow’s cheese in a nest of white grapes, three rolls, a chocolate mint, three glasses of Burgundy, and finally, as though it would absolve him of all else, he forced himself back through the menu to confront the oil-sodden salad that came with the quail. When his tray was removed, only the grapes remained.

÷ ÷ ÷

¤ Ian McEwan introduces ↓ ‘Sweet Tooth’ [2012]

Serena Frome, the beautiful daughter of an Anglican bishop, has a brief affair with an older man during her final year at Cambridge, and finds herself being groomed for the intelligence services. The year is 1972. Britain, confronting economic disaster, is being torn apart by industrial unrest and terrorism and faces its fifth state of emergency. The Cold War has entered a moribund phase, but the fight goes on, especially in the cultural sphere. Serena, a compulsive reader of novels, is sent on a ‘secret mission’ which brings her into the literary world of Tom Haley, a promising young writer. First she loves his stories, then she begins to love the man. Can she maintain the fiction of her undercover life? And who is inventing whom? To answer these questions, Serena must abandon the first rule of espionage – trust no one.

affair with an older man during her final year at Cambridge, and finds herself being groomed for the intelligence services. The year is 1972. Britain, confronting economic disaster, is being torn apart by industrial unrest and terrorism and faces its fifth state of emergency. The Cold War has entered a moribund phase, but the fight goes on, especially in the cultural sphere. Serena, a compulsive reader of novels, is sent on a ‘secret mission’ which brings her into the literary world of Tom Haley, a promising young writer. First she loves his stories, then she begins to love the man. Can she maintain the fiction of her undercover life? And who is inventing whom? To answer these questions, Serena must abandon the first rule of espionage – trust no one.

• Ian reads an excerpt from his latest book ↓ ‘Sweet Tooth’

• Chapter #1 . . .1

My name is Serena Frome (rhymes with plume) and almost forty years ago I was sent on a secret mission for the British Security Service. I didn’t return safely. Within eighteen months of joining I was sacked, having disgraced myself and ruined my lover, though he certainly had a hand in his own undoing.

I won’t waste much time on my childhood and teenage years. I’m the daughter of an Anglican bishop and grew up with a sister in the cathedral precinct of a charming small city in the east of England. My home was genial, polished, orderly, book-filled. My parents liked each other well enough and loved me, and I them. My sister Lucy and I were a year and a half apart and though we fought shrilly during our adolescence, there was no lasting harm and we became closer in adult life. Our father’s belief in God was muted and reasonable, did not intrude much on our lives and was just sufficient to raise him smoothly through the Church hierarchy and install us in a comfortable Queen Anne house. It overlooked an enclosed garden with ancient herbaceous borders that were well known, and still are, to those who know about plants. So, all stable, enviable, idyllic even. We grew up inside a walled garden, with all the pleasures and limitations that implies.

The late sixties lightened but did not disrupt our existence. I never missed a day at my local grammar school unless I was ill. In my late teens there slipped over the garden wall some heavy petting, as they used to call it, experiments with tobacco, alcohol and a little hashish, rock and roll records, brighter colors and warmer relations all round. At seventeen my friends and I were timidly and delightedly rebellious, but we did our schoolwork, we memorized and disgorged the irregular verbs, the equations, the motives of fictional characters. We liked to think of ourselves as bad girls, but actually we were rather good. It pleased us, the general excitement in the air in 1969. It was inseparable from the expectation that soon it would be time to leave home for another education elsewhere. Nothing strange or terrible happened to me during my first eighteen years and that is why I’ll skip them.

Left to myself I would have chosen to do a lazy English degree at a provincial university far to the north or west of my home. I enjoyed reading novels. I went fast—I could get through two or three a week—and doing that for three years would have suited me just fine. But at the time I was considered something of a freak of nature—a girl who happened to have a talent for mathematics. I wasn’t interested in the subject, I took little pleasure in it, but I enjoyed being top, and getting there without much work. I knew the answers to questions before I even knew how I had got to them. While my friends struggled and calculated, I reached a solution by a set of floating steps that were partly visual, partly just a feeling for what was right. It was hard to explain how I knew what I knew. Obviously, an exam in maths was far less effort than one in English literature. And in my final year I was captain of the school chess team. You must exercise some historical imagination to understand what it meant for a girl in those times to travel to a neighboring school and knock from his perch some condescending smirking squit of a boy. However, maths and chess, along with hockey, pleated skirts and hymn-singing, I considered mere school stuff. I reckoned it was time to put away these childish things when I began to think about applying to university. But I reckoned without my mother . . .

. . . more reading [in Denmark]⇒

It was a pleasant break in routine to travel down to Brighton one unseasonably warm morning in mid-October, to cross the cavernous railway station and smell the salty air and hear the falling cries of herring gulls. I remembered the word from a summer Shakespeare production of Othello on the lawn at King’s. A gull. Was I looking for a gull? Certainly not. I took the dilapidated three-carriage Lewes train and got out at the Falmer stop to walk the quarter mile to the redbrick building site called the University of Sussex, or, as it was known in the press for a while, Balliol-by-the-Sea. I was wearing a red mini-skirt and black jacket with high collar, black high heels and a white patent leather shoulder bag on a short strap. Ignoring the pain in my feet, I swanked along the paved approach to the main entrance through the student crowds, disdainful of the boys – I regarded them as boys – shaggily dressed out of army surplus stores, and even more so of the girls with their long plain centre-parted hair, no make-up and cheesecloth skirts. Some students were barefoot, in sympathy, I assumed, with peasants of the undeveloped world. The very word «campus» seemed to me a frivolous import from the USA. As I self-consciously strode towards Sir Basil Spence’s creation in a fold of the Sussex Downs, I felt dismissive of the idea of a new university. For the first time in my life I was proud of my Cambridge and Newnham connection. How could a serious university be new? And how could anyone resist me in my confection of red, white and black, intolerantly scissoring my way towards the porters’ desk, where I intended to ask directions.

I entered what was probably an architectural reference to a quad. It was flanked by shallow water features, rectangular ponds lined with smooth river-bed stones. But the water had been drained off to make way for beer cans and sandwich wrappers. From the brick, stone and glass structure ahead of me came the throb and wail of rock music. I recognised the rasping, heaving flute of Jethro Tull. Through the plate-glass windows on the first floor I could see figures, players and spectators, hunched over banks of table football. The students’ union, surely. The same everywhere, these places, reserved for the exclusive use of lunk-headed boys, mathematicians and chemists mostly. The girls and the aesthetes went elsewhere. As a portal to a university it made a poor impression. I quickened my pace, resenting the way my stride fell in with the pounding drums. It was like approaching a holiday camp.

. . .

With a pearly pink painted nail I tapped lightly on the door and, at the sound of an indistinct murmur or groan, pushed it open. I was right to have prepared myself for disappointment. It was a slight figure who rose from his desk, slightly stooped, though he made the effort to straighten his back as he stood. He was girlishly slender, with narrow wrists and his hand when I shook it seemed smaller and softer than mine. Skin very pale, eyes dark green, hair dark brown and long, and cut in a style that was almost a bob. In those first few seconds I wondered if I’d missed a trans-sexual element in the stories. He wore a collarless shirt made of flecked white flannel, tight jeans with a broad belt and scuffed leather boots. I was confused by him. The voice from such a delicate frame was deep, without regional accent, pure and classless.

“Let me clear these things away so you can sit.”

He shifted some books from an armless soft chair. I thought, with a touch of annoyance, that he was letting me know that he had made no special preparations for my arrival.

“Was your journey down all right? He said Would you like some coffee?”

The journey was pleasant, I told him, and I didn’t need coffee.

He sat down at his desk and swivelled his chair to face me, crossed an ankle over a knee and with a little smile opened out his palms in an interrogative manner. “So, Miss Frome …”

“It rhymes with plume. But please call me Serena.”

He cocked his head to one side as he repeated my name. Then his eyes settled softly on mine and he waited. I noted the long eyelashes. I’d rehearsed this moment and it was easy enough to lay it all out for him. Truthfully. The work of Freedom International, its wide remit, its extensive global reach, its open-mindedness and lack of ideology. He listened to me, head still cocked, and with a look of amused scepticism, his lips quivering slightly as though at any moment he was ready to join in or take over and make my words his own, or improve upon them. He wore the expression of a man listening to an extended joke, anticipating an explosive punchline with held-in delight that puffs and puckers his lips. As I named the writers and artists the Foundation had already helped, I fantasised that he had already seen right through me and had no intention of letting me know. He was forcing me to make my pitch so he could observe a liar at close hand. Useful for a later fiction. Horrified, I pushed the idea away and forgot about it. I needed to concentrate. I moved on to talk about the source of the Foundation’s wealth. Max thought Haley should be told just how rich Freedom International was.

Everything I had said so far had been the case, easily verified. Now I took my first tentative step into mendacity. “I’ll be quite frank with you,” I said. “I sometimes feel Freedom International doesn’t have enough projects to throw its money at.”

“How flattering then,” Haley said. Perhaps he saw me blush because he added, “I didn’t mean to be rude.”

“You misunderstand me, Mr Haley …”

“Tom.”

“Tom. Sorry. I put that badly. What I meant was this. There are plenty of artists being imprisoned or oppressed by unsavoury governments. We do everything we can to help these people and get their work known. But, of course, being censored doesn’t necessarily mean a writer or sculptor is any good. For example, we’ve found ourselves supporting a terrible playwright in Poland simply because his work is banned. And we’ll go on supporting him. And we’ve bought up any amount of rubbish by an imprisoned Hungarian abstract impressionist. So the steering committee has decided to add another dimension to the portfolio. We want to encourage excellence wherever we can find it, oppressed or not. We’re especially interested in young people at the beginning of their careers …”

“And how old are you, Serena?” Tom Haley leaned forward solicitously, as if asking about a serious illness.

I told him. He was letting me know he was not to be patronised. And it was true, in my nervousness I had taken on a distant, official tone. I needed to relax, be less pompous, I needed to call him Tom. I realised I wasn’t much good at any of this. He asked me if I’d been at university. I told him, and said the name of my college.

“What was your subject?”

I hesitated, I tripped over my words. I hadn’t expected to be asked, and suddenly mathematics sounded suspect and without knowing what I was doing I said, “English.”

He smiled pleasantly, appearing pleased at finding common ground. “I suppose you got a brilliant first?”

“A two one actually.” I didn’t know what I was saying. A third sounded shameful, a first would have set me on dangerous ground. I had told two unnecessary lies. Bad form. For all I knew, a phone call to Newnham would establish there had been no Serena Frome doing English. I hadn’t expected to be interrogated. Such basic preparatory work, and I’d failed to do it. Why hadn’t Max thought of helping me towards a decent watertight personal story? I felt flustered and sweaty, I imagined myself jumping up without a word, snatching up my bag, fleeing from the room.

Tom was looking at me in that way he had, both kindly and ironic. “My guess is that you were expecting a first. But listen, there’s nothing wrong with a two one.”

“I was disappointed,” I said, recovering a little. “There was this, um, general, um …”

“Weight of expectation?”

Our eyes met for a little more than two or three seconds, and then I looked away. Having read him, knowing too well one corner of his mind, I found it hard to look him in the eye for long. I let my gaze drop below his chin and noticed a fine silver chain around his neck.

“So you were saying, writers at the beginning of their careers.” He was self-consciously playing the part of the friendly don, the teacher coaxing a nervous applicant through her entrance interview. I knew I had to get back on top.

I said, “Look, Mr Haley …”

“Tom.”

“I don’t want to waste your time. We take advice from very good, very expert people. They’ve given a lot of thought to this. They like your journalism, and they love your stories. Really love them. The hope is …”

“And you. Have you read them?”

“Of course.”

“And what did you think?”

“I’m really just the messenger. It’s not relevant what I think.”

“It’s relevant to me. What did you make of them?”

The room appeared to darken. I looked past him, out of the window. There was a grass strip, and the corner of another building. I could see into a room like the one we were in, where a tutorial was in progress. A girl not much younger than me was reading aloud her essay. At her side was a boy in a bomber jacket, bearded chin resting in his hand, nodding sagely. The tutor had her back to me. I turned my gaze back into our room, wondering if I was not overdoing this significant pause. Our eyes met again and I forced myself to hold on. Such a strange dark green, such long child-like lashes, and thick black eyebrows. But there was hesitancy in his gaze, he was about to look away, and this time the power had passed to me.

I said very quietly, “I think they’re utterly brilliant.”

He flinched as though someone had poked him in the chest, in the heart, and he gave a little gasp, not quite a laugh. He went to speak but was stuck for words. He stared at me, waiting, wanting me to go on, tell him more about himself and his talent, but I held back. I thought my words would have more power for being undiluted. And I wasn’t sure I could trust myself to say anything profound. Between us a certain formality had been peeled away to expose an embarrassing secret. I’d revealed his hunger for affirmation, praise, anything I might give. I guessed that nothing mattered more to him. His stories in the various reviews had probably gone unremarked, beyond a routine thanks and pat on the head from an editor. It was likely that no one, no stranger at least, had ever told him that his fiction was brilliant. Now he was hearing it and realising that he had always suspected it was so. I had delivered stupendous news. How could he have known if he was any good until someone confirmed it? And now he knew it was true and he was grateful.

As soon as he spoke, the moment was broken and the room resumed its normal tone. “Did you have a favourite?”

It was such a stupid, sheepish excuse of a question that I warmed to him for his vulnerability. “They’re all remarkable,” I said. “But the one about the twin brothers, called “This Is Love”, is the most ambitious. I thought it had the scale of a novel. A novel about belief and emotion. And what a wonderful character Jean is, so insecure and destructive and alluring. It’s a magnificent piece of work. Did you ever think of expanding it into a novel, you know, filling it out a bit?”

He looked at me curiously. “No, I didn’t think of filling it out a bit.” The deadpan reiteration of my words alarmed me.

“I’m sorry, it was a stupid …”

“It’s the length I wanted. About fifteen thousand words. But I’m glad you liked it.”

Sardonic and teasing, he smiled and I was forgiven, but my advantage had dimmed. I had never heard fiction quantified in this technical way. My ignorance felt like a weight on my tongue.

I said, “And ‘Lovers’, the man with the shop-window mannequin, was so strange and completely convincing, it swept everyone away.” It was now liberating to be telling outright lies. “We have two professors and two well-known reviewers on our board. They see a lot of new writing. But you should have heard the excitement at the last meeting. Honestly, Tom, they couldn’t stop talking about your stories. For the first time ever the vote was unanimous.”

The little smile had faded. His eyes had a glazed look, as though I was hypnotising him. This was going deep.

“Well,” he said, shaking his head to bring himself out of the trance. “This is all very pleasing. What else can I say?” Then he added, “Who are the two critics?”

“We have to respect their anonymity, I’m afraid.”

“I see.”

He turned away from me for a moment and seemed lost in some private thought. Then he said, “So, what is it you’re offering, and what do you want from me?”

“Can I answer that by asking you a question? What will you do when you’ve finished your doctorate?”

“I’m applying for various teaching jobs, including one here.”

“Full time?”

“Yes.”

“We’d like to make it possible for you to stay out of a job. In return you’d concentrate on your writing, including journalism if you want.”

He asked me how much money was on offer and I told him. He asked for how long and I said, “Let’s say two or three years.”

“And if I produce nothing?”

“We’d be disappointed and we’d move on. We won’t be asking for our money back.”

He took this in and then said, “And you’d want the rights in what I do?”

“No. And we don’t ask you to show us your work. You don’t even have to acknowledge us. The Foundation thinks you’re a unique and extraordinary talent. If your fiction and journalism get written, published and read, then we’ll be happy. When your career is launched and you can support yourself we’ll fade out of your life. We’ll have met the terms of our remit.”

He stood up and went round the far side of his desk and stood at the window with his back to me. He ran his hand through his hair and muttered something sibilant under his breath that may have been “Ridiculous”, or perhaps, “Enough of this”. He was looking into the same room across the lawn. Now the bearded boy was reading his essay while his tutorial partner stared ahead of her without expression. Oddly, the tutor was speaking on the phone.

Tom returned to his chair and crossed his arms. His gaze was directed across my shoulder and his lips were pressed shut. I sensed he was about to make a serious objection.

I said, “Think it over for a day or two, talk to a friend … Think it through.”

He said, “The thing is …” and he trailed away. He looked down at his lap and he continued. “It’s this. Every day I think about this problem. I don’t have anything bigger to think about. It keeps me awake at night. Always the same four steps. One, I want to write a novel. Two, I’m broke. Three, I’ve got to get a job. Four, the job will kill the writing. I can’t see a way round it. There isn’t one. Then a nice young woman knocks on my door and offers me a fat pension for nothing. It’s too good to be true. I’m suspicious.”

“Tom, you make it sound simpler than it is. You’re not passive in this affair. The first move was yours. You wrote these brilliant stories. In London people are beginning to talk about you. How else do you think we found you? You’ve made your own luck with talent and hard work.”

The ironic smile again, the cocked head – progress.

He said, “I like it when you say brilliant.”

“Good. Brilliant, brilliant, brilliant.” I reached into my bag on the floor and took out the Foundation’s brochure. “This is the work we do. You can come to the office in Upper Regent Street and talk to the people there. You’ll like them.”

“You’ll be there too?”

“My immediate employer is Word Unpenned. We work closely with Freedom International and are putting money their way. They help us find the artists. I travel a lot or work from home. But messages to the Foundation office will find me.”

He glanced at his watch and stood, so I did too. I was a dutiful young woman, determined to achieve what was expected of me. I wanted Haley to agree now, before lunch, to be kept by us. I would break the news by phone to Max in the afternoon and by tomorrow morning I hoped to have a routine note of congratulation from Peter Nutting, unemphatic, unsigned, typed by someone else, but important to me.

“I’m not asking you to commit to anything now,” I said, hoping I didn’t sound like I was pleading. “You’re not bound to anything at all. Just give me the say-so and I’ll arrange a monthly payment. All I need is your bank details.”

The say-so? I’d never used that word in my life. He blinked in assent, but not to the money so much as to my general drift. We were standing less than six feet apart. His waist was slender and through some disorder in his shirt I caught a glimpse below a button of skin and downy hair above his navel.

“Thanks,” he said. “I’ll think about it very carefully. I’ve got to be in London on Friday. I could look in at your office.”

“Well then,” I said and put out my hand. He took it, but it wasn’t a handshake. He took my fingers in his palm and stroked them with his thumb, just one slow pass. Exactly that, a pass, and he was looking at me steadily. As I took my hand away, I let my own thumb brush along the length of his forefinger. I think we may have been about to move closer when there was a hearty, ridiculously loud knock on the door. He stepped back from me as he called, “Come in.” The door swung open and there stood two girls, centre-parted blonde hair, fading suntans, sandals and painted toenails, bare arms, sweet expectant smiles, unbearably pretty. The books and papers under their arms didn’t look at all plausible to me.

“Aha,” Tom said. “Our Faerie Queene tutorial.”

I was edging round him towards the door. “I haven’t read that one,” I said.

He laughed, and the two girls joined in, as if I’d made a wonderful joke. They probably didn’t believe me.

********

• Read another excerpt: → http://www.npr.org/2012/10/16/163024825/exclusive-first-read-ian-mcewans-sweet-tooth

÷ ÷ ÷

¤ Nutshell ⇓ [2016]

So here I am, upside down in a woman. Arms patiently crossed, waiting, waiting and wondering who I’m in, what I’m in for. My eyes close nostalgically when I remember how I once drifted in my translucent body bag, floated dreamily in the bubble of my thoughts through my private ocean in slow-motion somersaults, colliding gently against the transparent bounds of my confinement, the confiding membrane that vibrated with, even as it muffled, the voices of conspirators in a vile enterprise. That was in my careless youth. Now, fully inverted, not an inch of space to myself, knees crammed against belly, my thoughts as well as my head are fully engaged. I’ve no choice, my ear is pressed all day and night against the bloody walls. I listen, make mental notes, and I’m troubled. I’m hearing pillow talk of deadly intent and I’m terrified by what awaits me, by what might draw me in.

I’m immersed in abstractions, and only the proliferating relations between them create the illusion of a known world. When I hear “blue,” which I’ve never seen, I imagine some kind of mental event that’s fairly close to “green”—which I’ve never seen. I count myself an innocent, unburdened by allegiances and obligations, a free spirit, despite my meagre living room. No one to contradict or reprimand me, no name or previous address, no religion, no debts, no enemies. My appointment diary, if it existed, notes only my forthcoming birthday. I am, or I was, despite what the geneticists are now saying, a blank slate. But a slippery, porous slate no schoolroom or cottage roof could find use for, a slate that writes upon itself as it grows by the day and becomes less blank. I count myself an innocent, but it seems I’m party to a plot. My mother, bless her unceasing, loudly squelching heart, seems to be involved.

them create the illusion of a known world. When I hear “blue,” which I’ve never seen, I imagine some kind of mental event that’s fairly close to “green”—which I’ve never seen. I count myself an innocent, unburdened by allegiances and obligations, a free spirit, despite my meagre living room. No one to contradict or reprimand me, no name or previous address, no religion, no debts, no enemies. My appointment diary, if it existed, notes only my forthcoming birthday. I am, or I was, despite what the geneticists are now saying, a blank slate. But a slippery, porous slate no schoolroom or cottage roof could find use for, a slate that writes upon itself as it grows by the day and becomes less blank. I count myself an innocent, but it seems I’m party to a plot. My mother, bless her unceasing, loudly squelching heart, seems to be involved.

Seems, Mother? No, it is. You are. You are involved. I’ve known from my beginning. Let me summon it, that moment of creation that arrived with my first concept. Long ago, many weeks ago, my neural groove closed upon itself to become my spine and my many million young neurons, busy as silkworms, spun and wove from their trailing axons the gorgeous golden fabric of my first idea, a notion so simple it partly eludes me now. Was it me? Too self-loving. Was it now? Overly dramatic. Then something antecedent to both, containing both, a single word mediated by a mental sigh or swoon of acceptance, of pure being, something like—this? Too precious. So, getting closer, my idea was To be. Or if not that, its grammatical variant, is. This was my aboriginal notion and here’s the crux—is. Just that. In the spirit of Es muss sein. The beginning of conscious life was the end of illusion, the illusion of non-being, and the eruption of the real. The triumph of realism over magic, of is over seems. My mother is involved in a plot, and therefore I am too, even if my role might be to foil it. Or if I, reluctant fool, come to term too late, then to avenge it.

÷ ÷ ÷

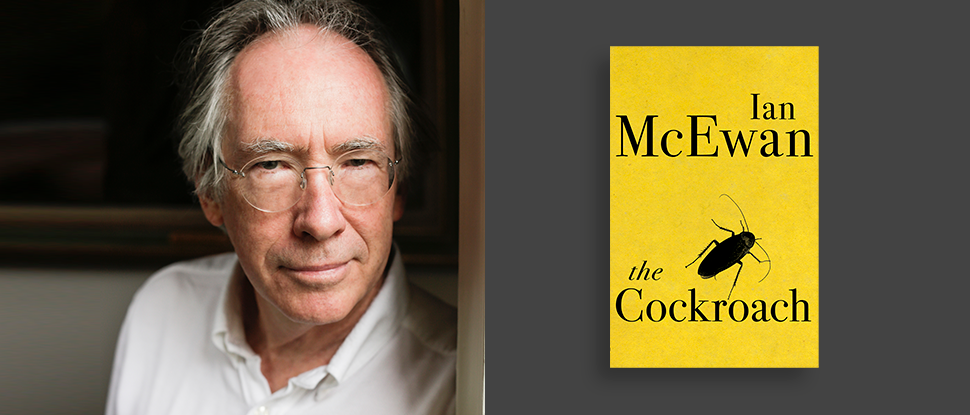

Cockroach ⇓ [2019]

Listen ⇑ ⇒ Read excerpt ⇐

A cool blog post there mate ! Thanks for posting .

Exactly what I was looking for, thankyou for posting .

Only wanna remark on few general things, The website design is perfect, the written content is really superb : D.

Thanks for your personal marvelous posting! I genuinely enjoyed reading it, you happen to be a great author.I will ensure that I bookmark your blog and will come back down the road. I want to encourage you continue your great posts, have a nice evening!

Only wanna state that this is extremely helpful, Thanks for taking your time to write this.