Rodrigo Paestra shots his unfaithful wife dead ↓ [10:30 P.M. Summer – directed by Jules Dassin, 1966]

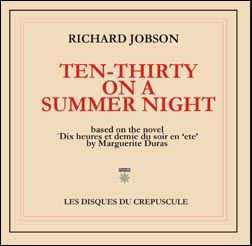

From 1983, 10.30 On a Summer Night is Richard Jobson‘s own adaption of texts from the passionate novel by French author Marguerite Duras (1914 – 1996), the story of a double love triangle set in Spain, where the runaway Rodrigo Paestra is hiding from the Guardia Civil…

I.- The hotel Pierre with his wife Maria and child Judith are accompanied by Claire, a friend of all but a secret lover of Pierre. Maria is aware of this secret. They arrive in a village, looked in a storm and held in disarray; as the hotel is so busy, they must sleep with other guests in the corridor. The police search for Rodrigo Paestra, who has committed a crime of passion: the murder of his young unfaithful wife… So much time went by that no trace of twilight was left in the sky. – Don’t expect any electricity tonight -the manager of the hotel had said- usually around here the storms are so violent that there’s no electricity all night. There was no electricity. There were going to be more storms, more sudden showers throughout the night. The sky was still low and small, still whipped by a very strong wind toward the west. The sky could be seen perfectly arched up to the horizon; and the limits of the storm could be seen too, trying to take over more of the clearer part of the sky. From the balcony where she was standing, Maria could see the whole expanse of the storm. They remained in the dining room. – I’ll be back – Maria had said. Behind her, in the corridor, all the children are now sleeping. Among them was Judith. And Maria turned around, she saw her asleep, her body outlined in the soft light of the oil lamps hooked up on the walls. – As soon as she’s asleep I’ll come back – Maria had told them. Judith was asleep. The hotel was full. The rooms, the corridors, and later on this hall would be still more crowded. There were more people in the hotel than in the whole district of the town. The town beyond which stretched deserted roads all the way to Madrid, toward which the storm was moving since five o’clock, bursting here and there, its clouds breaking and then mending again… to the point of exhaustion. There was no longer a single cafe open. – We’ll wait for you, Maria – Pierre had said. The town was small. It covered about five acres; all of it was crowded into an irregular but full neatly outlined shape. Beyond it, whichever way you turned, open country straights out bare, rolling. This was hardly noticeable that night, and yet, in the east, there seemed to be a sudden drop. A stream previously dried out would overflow in the morning. If you looked at the time, it was ten o’clock… in the evening… it was summer. Policemen were walking around under the hotel balconies. They must have been tired from searching. They dived their feet in the muddy streets. The crime had been committed a long time ago, hours ago, and they were talking about the weather.

– Rodrigo Paestra is on the rooftops.

Maria remembered: the rooftops were there; they were empty; they were shining dimly under the balcony where she was standing… empty.

They were waiting for her in the dining room, in the midst of clear tables, oblivious of her, looking at each other motionless. The hotel was full. There was no other place for them to look at each other except there.

Whistling started again at the other end of the town, well beyond the square in the direction of Madrid. Nothing happens. Policemen gathered at the street corner on the left, stopped, moved off again. It was just a break in a waiting period. The policemen walked by under the balcony and turned into another street. It was much later than ten. It was later than when she should have gone back to the dining- room, entered, moved in between and sat down and told them once more the surprising news:

– I’ve been told that Rodrigo Paestra is hiding on the roof-tops…

…I’ve been told that Rodrigo Paestra is hiding on the roof-tops…

…I’ve been told that Rodrigo Paestra is hiding on the roof-tops.

II. – The end of the storm

Policemen were walking around under the hotel balconies. They must have been tired from searching. They dived their feet in the muddy streets. The crime had been committed a long time ago, hours ago, and they were talking about the weather.

– Rodrigo Paestra is on the rooftops.

Maria remembered: the rooftops were there; they were empty; they were shining dimly under the balcony where she was standing… empty.

They were waiting for her in the dining room, in the midst of clear tables, oblivious of her, looking at each other motionless. The hotel was full. There was no other place for them to look at each other except there.

Whistling started again at the other end of the town, well beyond the square in the direction of Madrid. Nothing happens. Policemen gathered at the street corner on the left, stopped, moved off again. It was just a break in a waiting period. The policemen walked by under the balcony and turned into another street. It was much later than ten. It was later than when she should have gone back to the dining- room, entered, moved in between and sat down and told them once more the surprising news:

– I’ve been told that Rodrigo Paestra is hiding on the roof-tops…

…I’ve been told that Rodrigo Paestra is hiding on the roof-tops…

…I’ve been told that Rodrigo Paestra is hiding on the roof-tops.

II. – The end of the storm

Maria stopped singing. She waited. Yes, the sky had cleared, the storm had moved away; dawn would be beautiful … pale red. Rodrigo Paestra didn’t want to live. The song had brought no change to this shape; to this shape that had become less and less identifiable with anything but him; a shape without sharp angles, long and supple enough to be human, with a sudden roundness on top, a small surface of the head surging from the mass of the body: a man!

– Oh, I beg you… I beg you, Rodrigo Paestra…I beg you …I beg you.

– HEY THERE! . . . HEY THERE..!

Without stopping, softly, as she would with an animal, louder and louder, she had closed the balcony windows behind her. Somebody had moaned and fallen asleep. Then, the police came. There they were… They were talking … more than the others. They talked about the weather. Maria, leaning over the railing of the balcony, could see them. One of them raised his eyes, looked into the sky, didn’t see Maria and said the storm had definitely vanished from these parts.

Maria called again as she would call an animal.

– YOU ARE AN IDIOT – Maria shouted – YOU ARE AN IDIOT

No one had awaked up in the town; nothing happened. The shape had remained wrapped in its stupidity. In the hotel, nothing had moved. She had to wait.

– Idiot; idiot – she now said softly, being careful – Idiot!

The patrol came again. Maria stopped shouting insults.

The patrol passed…

– HEY, HEY … RODRIGO PAESTRA … HEY, HEY!

He was there … in the same place; he was there.

A blue light now fell from the sky. It was impossible that he didn’t see this woman shape leaning toward him as no one ever had on the hotel balcony. Even if he wanted to die; even if he wanted this particular fate, he could answer her one last time.

Again the policemen of hell, they went by. Then there was silence. Behind Maria all the blue sky lit up the hallway; but Claire and Pierre were sleeping … apart.

Did he lose hope of seeing her again while she had turned? Something had emerged from the black shroud; something white: a face… or a hand… it was he … Rodrigo Paestra … it was he, Rodrigo Paestra! They confronted each other; it was a face it was a face. They were face to face and looked at each other.

It was ten to two. An hour and a half before his death, Rodrigo Paestra had accepted to see her. Maria raised her hand to say hello. She waited. A slow slow hand came out of the shroud, rose and also made the gesture of mutual understanding. Then, both of the hands fell down.

At last the horizon was completely cleared by the storm, like a blade it was cutting the wheat fields. A warm wind rose and began to dry the streets. The weather was beautiful, just as it would be beautiful during the day. The night was still whole. Perhaps solutions could be found to the problems of conscience . . . Perhaps.

Serenely Maria raised her hand again … He answered … again … again … AGAIN … AGAIN … Oh, how marvelous again! AGAIN … AGAIN!

IV.- The road to MadridThere was no village in sight; and there was total silence as soon as Maria turned off the engine. When Maria turned around Rodrigo Paestra was getting out of his shroud.

It is cold in Spain on stormy nights an hour before dawn. He was the first to speak:

– Where are we? … Where are we? … Where are we?… Where are we? … Where are we? – The road to Madrid . . . The road to Madrid . . . The road to MadridV.- The kiss the dance & the death

• The Kiss, The Dance and the Death ↑ You might prefer to skip the long piano intro . . . Kiss me … Kiss me again Kiss me … Kiss me again It’s all over – It’s all over This is the end Maria … Maria … oh Maria! A man was dancing alone on the stage. The place was full; there were many tourists. The man danced well. The music took turns with his steps on the bare and dirty floor. He was surrounded by women in loud, hastily put on, faded dresses. They must have been dancing all afternoon, the height of summer with its overwork. Whenever the man stopped dancing, the band would play pasodobles and the man would sing them into a microphone. Plastered on his face he had at times a chalky laugh, and at times the mask of a loving languorous nauseous drunkenness that made an impression on his audience. In the room among the others, packed together like the others, Maria, Claire and Pierre were looking at the dancer. (The end of a storm . . .)÷ ÷ ÷ ÷ ÷

•→ ‘India Song’ ⇐

¤ Richard Jobson as a film maker . . .

♦→ 16 Years of Alcohol ⇐ [clip – 2003]

Richard Jobson’s directorial debut with this stylized psychological drama based on his own semi-autobiographical novel. Through voice-over narration and various flashback methods, troubled young man Frankie Mac (Kevin McKidd) recalls his childhood (played by Iain De Caestaecker as a boy) growing up in working-class Edinburgh. In the ’50s, his father (Lewis McCloud) was a hard-drinking good-timer and his long-suffering mother (Lisa May Cooper) eventually gave up on the family. As a teenager in the ’70s, the violent Frankie falls in with a street gang and tries to clean up to impress record store clerk Helen (Laura Fraser). After some fights with his old street thug enemy Miller (Stuart Sinclair Blyth), Frankie makes an another attempt to stop drinking at an AA meeting, where he meets Mary (Susan Lynch). ~ Andrea LeVasseur, Rovi

•→ A Woman in Winter [2006]

Micheal, an astronomer falls in love with a mysterious photographer Caroline. He gets so obsessed with his new found love, that he finds it hard to distinguish between what is real and what is fiction

•→ New town killers ⇐[2008 – trailer]

•→ The Journey [clip, 2009]

Richard Jobson and Emma Thompson’s short film about the brutal realities of sex trafficking. Made in conjunction with The Helen Bamber Foundation.

•→ The somnambulists ⇐[clip, 2012]

Comprised of fifteen short segments, The Somnambulists takes a critical view at Britain’s role in the war in Iraq. Each section is a monologue from a different character who reflects on their time at the front line, including flashbacks to their families and loved ones back at home.

The Somnambulists comes across as viciously anti-war, portraying very negative aspects of being on tour. The characters speak of loss, stress, depression, drug abuse, sleeplessness, loneliness, bullying and homesickness. They are pushed to the limit and overwhelmed by their experiences, be they soldiers, officers, or medics.

thanks for taking a time to help people with so great information, congratulations, your work is so dignifying.http://www.plactual.com

cool, i love it.http://www.acertemail.com

I don’t ordinarily comment but I gotta say regards for that post on this one.

Lovely just what I was looking for.Thanks to the author for taking his clock time on this one.

I have recently started a blog, the information you offer on this web site has helped me greatly. Thank you for all of your time & work.

Some really interesting details you have written. Aided me a lot, just what I was searching for : D.