Dixon first ran away from home when he was eleven. As he recalled in his autobiography, I Am the Blues, “I ran out in the country to a place 11 miles from home called Bovine, Mississippi…. It was nothing like I expected–man, you’re talking about a shack…. I thought our house was raggedy but … the house [I stayed] in had great big holes in the floor. You could see the hogs and chickens running around under the house.”

His first taste of country living also introduced him to hard work, something he would become more familiar with as he grew older. Although Dixon was happy when he got back home, his pre-teen and teen years were filled with travels and run-ins with the law. During the late 1920s and early 1930s, many men were riding the rails in search of work. Dixon soon found that “hoboing” was considered a crime, although, as he noted in his autobiography, it seemed that only black men were arrested for it.

Dixon was only twelve when he first landed in jail and was sent to a county farm for stealing some fixtures from an old torn-down house. He recalled in I Am the Blues: “That’s when I really learned about the blues. I had heard ‘em with the music and took ‘em to be an enjoyable thing but after I heard these guys down there moaning and groaning these really down-to-earth blues, I began to inquire about ‘em…. I really began to find out what the blues meant to black people, how it gave them consolation to be able to think these things over and sing them to themselves or let other people know what they had in mind and how they resented various things in life.”

About a year later Dixon was caught by the local authorities near Clarksdale, Mississippi, and arrested for hoboing. He was given thirty days at the Harvey Allen County Farm, located near the infamous Parchman Farm prison. At the Allen Farm, Dixon saw many prisoners being mistreated and beaten. According to his autobiography, the authorities who were “running the farm didn’t have no mercy–you talk about mean, ignorant, evil, stupid and crazy. [They] fouled up many a man’s life…. This was the first time I saw a man beat to death.”

About a year later Dixon was caught by the local authorities near Clarksdale, Mississippi, and arrested for hoboing. He was given thirty days at the Harvey Allen County Farm, located near the infamous Parchman Farm prison. At the Allen Farm, Dixon saw many prisoners being mistreated and beaten. According to his autobiography, the authorities who were “running the farm didn’t have no mercy–you talk about mean, ignorant, evil, stupid and crazy. [They] fouled up many a man’s life…. This was the first time I saw a man beat to death.”

Dixon himself was mistreated at the county farm, receiving a blow to his head that he said made him deaf for about four years. He managed to escape, though, and walked to Memphis, where he hopped a freight into Chicago. He stayed there briefly at his sister’s house, then went to New York for a short time before returning to Vicksburg.

In 1936, Dixon left Mississippi and headed to Chicago. He had worked several odd jobs to try and make ends meet. He soon took up boxing and won the Illinois State Golden Gloves Heavyweight Championship (Novice Division). Dixon turned professional as a boxer and worked briefly as Joe Louis’ sparring partner. After four fights, Dixon left boxing after getting into a fight with his manager over being cheated out of money.

Throughout the late 1930s, Dixon was singing in Chicago with various gospel groups. Around the same time, Leonard “Baby Doo” Caston gave Dixon his first musical instrument–a makeshift bass made out of an oil can and one string. Dixon, Caston, and some other musicians formed a group called the Five Breezes. They played around Chicago and in 1939 made a record that marked Dixon’s first appearance on vinyl.

Dixon had other problems, though, notably with the local draft board. His position was that black people had been exploited so much that they should not be obligated to serve in the armed forces. He spoke out on this issue frequently and with great force; eventually he was classified as unfit for military service and forbidden to work in any defense industry.

In 1946 Dixon and Caston formed the Big Three Trio, named after the wartime “Big Three” of U.S. president Franklin Roosevelt, British prime minister Winston Churchill, and Soviet political leader Joseph Stalin. Dixon by this time was singing and playing a regular upright bass. In 1951 after several years of successful touring and recording, the Big Three Trio disbanded.

Leonard and Phil Chess began recording the blues in the late 1940s and, over the next decade, Chess became what many consider to be the most important blues label in the world, releasing material by such blues giants as Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf and rhythm and blues artists like Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry. Many of the blues songs recorded at Chess were written, arranged, and produced by Willie Dixon.

Dixon’s first big break as a songwriter came when Muddy Waters recorded his “Hoochie Coochie Man” in 1954. When “Hoochie Coochie Man” became Waters’ biggest hit, reaching Number Three on the rhythm and blues charts, Dixon became the label’s top songwriter. Chess also released Waters’s recordings of Dixon’s “I Just Wanna Make Love to You” and “I’m Ready” in 1954, and they both became Top Ten R & B hits.

In 1955 Dixon charted his first Number One hit when Little Walter recorded “My Babe”, a song that became a blues classic. Songwriter Mike Stoller of Leiber and Stoller fame told Goldmine magazine, “If he’d only done ‘My Babe’ [and nothing else], I think his name would have gone down in the history of American popular music. He created the entire sound that we now know as the Chess sound, and as such, he’s one of the most important record producers ever in the history of popular music. What impressed me most about his songs were their economy, their simplicity and their depth.” One of Dixon’s most widely recorded songs, “My Babe” has been performed and recorded by artists as varied as the Everly Brothers, Elvis Presley, Ricky Nelson, the Righteous Brothers, Nancy Wilson, Ike and Tina Turner, and blues artists John Lee Hooker, Bo Diddley, and Lightnin’ Hopkins.

Dixon supplied Chess blues recording artists with songs for three years, from 1954 through 1956. At the end of 1956, however, he left the label over disputes regarding royalties and contracts. He continued to play on recording sessions at Chess, though, most notably providing bass on all of Chuck Berry’s sessions starting with the recording of “Maybelline” in 1955.

In 1957 Dixon joined the small independent Cobra Records, where he recorded such bluesmen as Otis Rush, Buddy Guy, and Magic Sam, creating what became known as the “West Side Sound.” According to Don Snowden in I Am the Blues, it was a blues style that “fused the Delta influence of classic Chicago blues with single-string lead guitar lines la B. B. King. The West Side gave birth to a less traditional, more modern blues sound and the emphasis placed on the guitar as a lead instrument ultimately proved to be a vastly influential force on the British blues crew in their formative stages.”

Gradually learning more about the music business, Dixon formed his own publishing company, Ghana Music, in 1957 and registered it with Broadcast Music Incorporated (BMI) to protect his copyright interest in his own songs. His “I Can’t Quit You Baby” was a Top Ten rhythm and blues hit for Otis Rush, but Cobra Records soon faced financial difficulties. By 1959 Dixon was back at Chess as a full-time employee.

The late 1950s were a difficult time for bluesmen in Chicago, even as blues music was gaining popularity in other parts of the United States. In 1959 Dixon teamed up with an old friend, pianist Memphis Slim, to perform at the Newport Folk Festival in Newport, Rhode Island. They continued to play together at coffee houses and folk clubs throughout the country and eventually became key players in a folk and blues revival among young white audiences that achieved its height in the 1960s.

Toward the end of the 1960s soul music eclipsed the blues in black record sales. Chess Records’ last major hit was Koko Taylor’s 1966 recording of Willie Dixon’s “Wang Dang Doodle.” Many prominent bluesmen had died, including Elmore James, Sonny Boy Williamson, Little Walter, and J.B. Lenoir. Chess Records was sold in 1969, and Dixon recorded his last session for the label in 1970.

Throughout the 1970s Dixon continued to write new songs, record other artists, and release his own performances on his own Yambo label. His busy performing schedule kept him on the road in the United States and abroad for six months out of the year until 1977, when his diabetes worsened and caused him to be hospitalized. He lost a foot from the disease but, after a period of recuperation, continued performing into the next decade.

Dixon resumed touring and regrouped the Chicago Blues All-Stars in the early 1980s. In 1983 he and his family moved to southern California, where Dixon began working on scores for movies. Dixon’s final two albums were well received, with the 1988 album Hidden Charms winning a Grammy Award for best traditional blues recording. In 1989 he recorded the soundtrack for the film Ginger Ale Afternoon, which also was nominated for a Grammy.

When Dixon died in 1992 at the age of 76, the music world lost one of its foremost blues composers and performers. From his musical roots in the Mississippi Delta and Chicago, Dixon created a body of work that reflected the changing times in which he lived.

◊ ‘Walkin’ the Blues’ ↓

Man, slow down – we’ll get there, take your time, don’t walk so fast – stay on your roller I don’t blame pepole saying «walking the blues», walking the blues’cause man, this is it. Now i think I’ll relax – That’s the way to relax.. Now watch this, Boy, is it hot today! All you gotta do is put one foot in the front door and keep on walking, Walking the blues. That’s what i call [. . .?] I hope my old lady is home, when i get there. All this walking, I don’t need my mother-in-law, I mean my wife, my mother-in-law, she’s allways there so we’ll just keep walking on.◊ → ‘Sittin’ & Cryin’ The Blues‘ ↓ [1963]

All I do is think of you – I sit and cry and sing the blues Oh, there’s no one to depend on since my baby’s love has been gone

Broken-hearted and lonesome, too – I sit and cry and sing the blues Blues all in my bloodstream – Blues all in my heart

Blues all in my soul – I got blues all in my bones Oh, there’s no one to talk to and my love is so true

Lord, I don’t know what to do – I sit and cry and sing the blues I sit and cry and sing the blues – I sit and cry and sing the blues.

◊ ‘I Love The Life I Live’ ↓

I see you watching me just like a hawk – I don’t mind about the things you talk

But if you touch me somethin’s got to give – I live the life I love and I love the life I live

Don’t worry about me if you think I’m high – I feel good and divine

The pretty girls move me at their will – I live the life I love and I love the life I live

I took my chance and I had my thrill – I live the life I love and I love the life I live

w/ Memphis Slim ↓ ‘Nervous’ (1962)

When my b-b-baby kiss me, she s-s-squeeze me real tight

She l-l-look me in the eyes and say, »Ev’ry-th-thing’s alright’

But I get nervous … M-m-man. Do I get nervous!

I’m a n-n-nervous man and I t-t-tremble all in my bones

Now every time she squeeze me make me feel so good

I want t-t-to tell everybody in the neighborhood

But I get the n-nervous man … Man, do I get nervous!

I’m a n-n-nervous man and I t-t-tremble all in my bones

Now every time she kiss me make me feel so good

I wanna t-t-talk all about it in the neighborhood

But I get the n-nervous man … Man, do I get nervous!

I’m a n-n-nervous man and I t-t-tremble all in my bones

◊ ‘Built for Comfort’ ↓

Some folks are built like this – Some folks are built like that

But the way I’m built – Now, don’t you call me fat

Beause I’m-a built for comfort; I ain’t a-built for speed

And I got ev’rything that the little girls need

You know I don’t have diamonds – I don’t have gold

I got a lot of love to satisfy your soul

Beause I’m-a built for comfort; I ain’t a-built for speed

But I got ev’rything that the little girls need

w/ Koko Taylor & Buddy Guy ↓ ‘Wang Wang Doodle’

Tell Automatic Slim , tell Razor Totin’ Jim

Tell Butcher Knife Totin’ Annie, tell Fast Talking Fanny

We gonna pitch a ball, a down to that union hall

We gonna romp and tromp till midnight

We gonna fuss and fight till daylight

We gonna pitch a wang dang doodle all night long

All night long – All night long – All night long

Tell Kudu-Crawlin’ Red, tell Abyssinian Ned

Tell ol’ Pistol Pete, everybody gonna meet

Tonight we need no rest, we really gonna throw a mess

We gonna to break out all of the windows,

we gonna kick down all the doors

We gonna pitch a wang dang doodle all night long

All night long – All night long – All night long

Tell Fats and Washboard Sam, that everybody gonna to jam

Tell Shaky and Boxcar Joe, we got sawdust on the floor

Tell Peg and Caroline Dye, we gonna have a time

When the fish scent fill the air, there’ll be snuff juice everywhere

We gonna pitch a wang dang doodle all night long

All night long … All night long … All night long . . .

÷ ÷ ÷ ÷ ÷ ÷

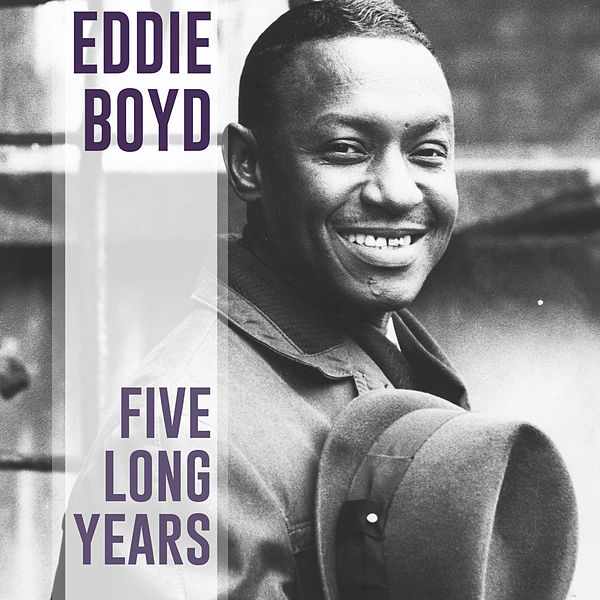

¤ Eddie Boyd [1914-1994]

Few postwar blues standards have retained the universal appeal of Eddie Boyd‘s «Five Long Years.» Cut in 1951, Boyd’s masterpiece has attracted faithful covers by B.B. King, Muddy Waters, Jimmy Reed, Buddy Guy, and too many other bluesmen to recount here. But Boyd’s discography is filled with evocative compositions, often full of after-hours ambience.

Like so many Chicago blues stalwarts, Boyd hailed from the fertile Mississippi Delta. The segregationist policies that had a stranglehold on much of the South didn’t appeal to the youngster, so he migrated up to Memphis (where he began to play the piano). In 1941, Boyd settled in Chicago, falling in with the «Bluebird beat» crowd that recorded for producer Lester Melrose.

⇐

If you ever been mistreated, then you know just what I’m talkin’ aboutIf you ever been mistreated, then you know just what I’m talkin’ about

I worked five long years for one woman, and she had the nerve to put me out I got a job at a steel mill, truckin’ steel like a slave

I got a job at a steel mill, truckin’ steel like a slave

For five long years every Friday, I went straight home with all of my pay If you ever been mistreated, you know just what I’m talkin’ about

If you ever been mistreated, you know just what I’m talkin’ about

I worked five long years for a woman, and she had the nerve to put me out

◊ ‘Third Degree’ ↓

Got me accused of peeping, I can’t see a thingGot me accused of petting, I can’t even raise my hand

Bad luck, bad luck is killing me Well I just can’t stand no more of this third degree

Got me accused of murder, I ain’t harmed a man

Got me accused of forgery, I can’t even write my name Got me accused of taxes, I ain’t got a dime

Got me accused of children, and ain’t nary one of them was mine Got me accused of taxes, I ain’t got a dime

Got me accused of children, and ain’t nary one of them was mine

Deja un comentario