¤ Liz Lochhead ⇓

⇒Makar Liz Lochhead was born in 1947 in Motherwell, from where the family moved to the nearby village of Newarthill. It was a “very normal, very Scottish, very proddy, posh working-class / lower middle-class life”. Everyone in family read a lot and used the public library as “there wasn’t much else to do”.

Lochhead enrolled at Glasgow School of Art in 1965, and later taught art in schools for eight years. “When you’re drawing, time passes incredibly quickly, you’ve been in another kind of world. The best bits of writing are like that.”

•→ Liz Lochhead reads her poem ⇔ ‘My Rival’s House’⇐

♦ ‘Men Talk’ ⇓

Women rabbit rabbit rabbit

Women tattle and titter – Women prattle

Women waffle and witter

Men Talk. Men Talk.

Women into Girl Talk

About Women’s Trouble

Trivia ‘n’ Small Talk

They yap and they babble

Men Talk. Men Talk.

Women gossip Women giggle

Women niggle-niggle-niggle

Men Talk.

Women yatter – women chatter

Women chew the fat, women spill the beans

Women aint been takin’

The oh-so Good Advice in them

Women’s Magazines.

A Man Likes a Good Listener.

Oh yeah

I like A Woman who likes me enough

Not to nitpick, not to nag and

Not to interrupt ‘cause I call that treason

A woman with the Good Grace

To be struck dumb

By me Sweet Reason. Yes – Remember

A Man Likes a Good Listener

A Real Man Likes a Real Good Listener

Women yap yap yap

Verbal Diarrhoea is a Female Disease

Women she spread she rumours round she

Like Philadelphia Cream Cheese

Oh

Bossy Women Gossip

Girlish Women Giggle

Women natter, women nag

Women niggle niggle niggle

Men Talk.

Men _Think First _ Speak Later

Men Talk

♦ Liz reads «The Choosing» plus a couple of verses by Robert Burns ↓

We were first equal Mary and I

with the same coloured ribbons in mouse-coloured hair

and with equal shyness

we curtseyed to the lady councillor

for copies of Collins’s Children Classics.

First equal, equally proud.

Best friends too Mary and I

a common bond in being cleverest (equal)

in our small school’s small class.

I remember

the competition for top desk

or to read aloud the lesson

at school service.

And my terrible fear

of her superiority at sums.

I remember the housing scheme

Where we both stayed.

The same house, different homes,

where the choices were made.

I don’t know exactly why they moved,

but anyway they went.

Something about a three-apartment

and a cheaper rent.

But from the top deck of the high school bus

I’d glimpse among the others on the corner

Mary’s father, mufflered, contrasting strangely

with the elegant greyhounds by his side.

He didn’t believe in high school education,

especially for girls,

or in forking out for uniforms.

Ten years later on a Saturday —

I am coming home from the library —

sitting near me on the bus,

Mary

with a husband who is tall,

curly haired, has eyes

for no one else but Mary.

Her arms are round the full-shaped vase

that is her body.

Oh, you can see where the attraction lies

in Mary’s life —

not that I envy her, really.

And I am coming from the library

with my arms full of books.

I think of the prizes that were ours for the taking

and wonder when the choices got made

we don’t remember making.

♦ →Kidspoem / Bairnsang ↓

This poem, in Scots and English, starts in Scots, and then changes to English with the words:

«it was January and a really dismal day the first day I went to school . . .»it wis January

and a gey driech day

the first day Ah went to the school

so my Mum happed me up in ma

good navy-blue napp coat wi the rid tartan hood

birled a scarf aroon ma neck

pu’ed oan ma pixie an’ my pawkies

it wis that bitter

said noo ye’ll no starve

gie’d me a wee kiss and a kid-oan skelp oan the bum

and sent me aff across the playground

tae the place A’d learn to say

it was January

and a really dismal day

the first day I went to school

so my mother wrapped me up in my

best nay-blue top coat with the red tartan hood,

twirled a scarf around my neck,

pulled on my bobble-hat and mittens

it was so bitterly cold

said now you won’t freeze to death

gave me a little kiss and a pretend slap on the bottom

and sent me off across the playground

to the place I’d learn to forget to say

it wis January

and a gey driech day

the first day Ah went to the school

so my Mum happed me up in ma

good navy-blue napp coat wi the rid tartan hood,

birled a scarf aroon ma neck,

pu’ed oan ma pixie and’ ma pawkies

it wis that bitter.

Oh saying it was one thing

But when it came to writing it

In black and white

The way it had to be said

Was as if you were posh, grown-up, male, English and dead.

•→»Trouble is not my middle name» ⇔ (written from a child’s perspective)

¤ Ivor Cutler ⇓ [1923-2006]

The Best Thing about being dead is that you no longer have to say, «I wish I were dead» The Best Thing about being alive is that you can still say, «I wish I were dead» Bread is a word – Butter is a word You cannot place them together: it is «bread and butter», or «butter on bread». Yet, if you search between the bread and the butter you will find neither «and« nor «on« Just butter – Just bread.♦→ «A Doughnut In My Hand» ⇐

I need nothing – I’ve everything I need

I walk along the dusty road – a doughnut in my hand

The sun is round and yellow and it shines upon my feet

I’ve walked a hundred yards and I’m not the least bit tired

I need nothing – I’ve everything I need

I walk along the dusty road – a doughnut in my hand

The cloud is white upon the sky

as white as a woman’s skin

I’ve walked another hundred yards

and I’m not the least bit tired

I need nothing – I’ve everything I need

I walk along the dusty road – a doughnut in my hand

I bumped into a dairy bush with cows on every twig

I squeezed myself a glass of milk – my thirst went up like smoke

I need nothing – I’ve everything I need

I walk along the dusty road a _

I stumbled by a sailor who was lying by the road

I kissed his lips and made him wince and then I stumbled on

I need nothing – I’ve everything I need

I walk along the dusty road – a doughnut in my hand

I spied a silken coffin – the lid was open wide

I wrapped my shirt right round my legs

And laid down flat inside

I need nothing – I’ve everything I need

I lie upon the coffin – A doughnut in my hand

Ivor‘s early childhood memories… Some words have been linked to their meanings: just click.

◊ Episode 1 ↓ [Listen & read]

We walked around eating porridge as taught, or sat looking glum on the velvet suite staring at the onyx clock which would not tell the time any more. But it was decorative, like the Parthenon, except that it held St Paul’s dome at the middle. If you put your finger in at the back, you could make it chime by listing the hammers, then letting them fall on to stop the copper wires down below. Granda’ did it at least once every hour, and had to be restrained during the night, particularly when losing at whist or nine-dot dominoes.

Although it had a pattern, crumbs on the carpet weren’t wanted. We were obliged to kneel and eat cream crackers with butter and Gouda with a white plate, with our heads inside the sideboard. This was a treat! Because there was room for four and in the luminous gloom we whispered jokes so that when laughter rose, showers of buttery spitty crumbs flew out our mouths like starlings and lodged against the aromatic mahogany, second magnitude stars. If somebody choke, you got quite big bits.

The children micturated on to a large sponge which sat by the window. If it was boys, the girls had to look hard at their sewing with their fingers by their ears. If it was girls, the boys had to clasper in a group in a far corner whilst Grandpa’ showed them a postcard of the Rokeby Venus in colour and explained it to them till the girls’ knickers were safety up again and hidden. The adults just did it out the window, standing or sitting, according to piss or sex. Voiding the bowels in those days was unheard of; people just kept it in. Grandma’ wrung the sponge out the window twice a day in summer, seven in winter, never without a grim twinkle in her eyes, or at least what seemed to be a grim twinkle.

¶ Life in a Scotch Sitting Room, part II ↓ Episode 2

‘Come lads, what shall we play at today?’ whispered Grandpa, busily dandling us.

‘The seaside! The seaside!’ we shouted.

‘Down the River Clyde!’ I added, for which impertinence I received a mighty buffet, bleeding my tender nose with his vast white knuckle. How was I to know that I was mouthing obscenity? But the blood soon dried and I had the pleasure of picking the clots.

He rose, and we slid over the edge of his kilt. Out the cupboard came the tin lid of Troon sand, sadly depleted, and two milk jugs with decent spouts. We stood in a rough quadrant holding forth our left hands according to custom, but I didn’t mind as I was left-handed, even though my co-ordination was poor owing to the myelin shortage. Grandpa moved round placing a grain of sand on every hand. Then he started a second round, and a third. And I held the big quartz grain, almost twice the size. He spotted the envy on other faces.

‘I bled his neb,‘ he grunted.

We went off to play. Each girl chose a boy to sit cross-legged before as she knitted. Her job was to blow into his face and hair like a breeze. Grandma came round with a lump of coarse salt and scraped a few grains on to every girl’s tongue. If a fleck of spit hit you, the illusion was complete. Then she filled a milk jug with treacle and poured it back and forward from jug to jug, spilling barely a dribble. It sounded like estuary waves, which was the only kind we knew.

There were many sorts of games to play with our three grains of sand: juggling, building castles, digging holes, making faces, reflecting light to dazzle Grandpa as he sat muttering and picking at his sporran, knocking them together to see if they would fetch the stonechat from his bush in the garden. I used to be able to sniff them up one nostril, tilt my head and catch them out the other.

When it became too dark to see, the sand was collected in. Grandpa never counted – we were on our honour. The first to hand in his sand got sucking spilled treacle out the tufts of the carpet. I am convinced the girls enjoyed the day’s outing as much as we did, in a placid way. Then we had tea.

∇ Episode 6

←’Scotland gets its brains from the herring,’ said Grandpa, and we all nodded our heads with complete incomprehension. Sometimes, for a treat, we got playing with their heads; glutinous bony affairs, without room for brains, and a look of lust on their narrow soprano jaws.

The time I lifted the lid of the midden on a winter night, and there, a cool blue gleam – herring heads . . . Other heads do not gleam in the dark. So perhaps Grandpa was right.

To make sure we ate the most intelligent herring, he fished the estuary. Planted a notice, ‘Literate herring this way!‘ below the water-line at the corner where it met the sea. The paint for the notice was made of crushed heads. Red-eyed herring, sore from reading, would round the corner, read the notice and sense the estuary water, bland and eye-easing. A few feet brought them within the confining friendliness of his manilla net and a purposeful end.

There was only one way to cook it: a deep batter of porridge left from breakfast was patted round and it was fed on to the hot griddle athwart the coal fire. In seconds, a thick aroma leaned around and bent against the walls. We lay down and dribbled on the carpet. Also, the air was fresher. Time passed. In exactly twenty-five minutes the porridge cracked, and juice steamed through with a glad fizz. We ate the batter first to take the edge off our appetites, so that we could eat the herring with respect. Which we did, including the bones.

After supper, assuming the herring to have worked, we were asked questions. In Latin, Greek and Hebrew, we had to know the principal parts of verbs. In Geography, the five main glove-manufacturing towns in the Midlands, and in History, the development of Glasgow’s sewage system.

There’s nothing quite like a Scotch education. One is left with an irreparable debt. My head is full of irregular verbs still.

♦ ‘Go and sit upon the grass’ ↓ [Robert Wyatt’s cover]

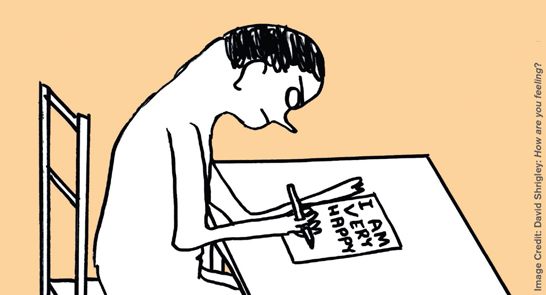

Go and sit upon the grass and I shall come and sit beside you … Then we shall talk While we talk I’ll hit your head with a nail to make you understand me … Go and sit upon the grass and I shall come and sit beside you … Do not mind if I thump you when I am talking to you I have something important to say … Go and sit upon the grass and I shall come and sit beside you … When I’m gone, you can feel the lumps upon your head and think about what I said, and think about what I said Go and sit upon the grass and feel your lumpsΘ ‘I’m Happy’ ⇑ I’m happy and I’ll punch the man who says I’m not . . . [Ouch!]

◊ ‘A Red Flower’ ↓ [animation by David Shrigley]

‘Good morning, madam.’ ‘Good morning. I wish to buy a red flower.’ ‘Certainly, madam. Is there any particular variety of flower you had in mind?’ ‘I wish to buy a red flower.’ ‘Certainly, madam. A large red flower, or a small one?’ ‘Size is a matter of indifference to me, just so it is a red flower.’ ‘Certainly, madam. A hyacinth, a crocus, or a daffodil, or perhaps one of those charming lobelias, or we have narcissus, old man’s beard and dandelion, and colts foot too, of course.’ ‘I don’t really mind, just so it is a red flower.’ ‘Certainly, madam. Pray be seated. Our Miss Jones will attend you… Miss Jones, madam wishes to purchase a red flower.’ ‘Madam.’ ‘I should like a red flower.’ ‘Certainly, madam. Any particular variety?’ ‘Yes, red.’ ‘Ah! A large or small flower, madam?’ ‘Size is a matter of indifference to me. Just so it is red.’ ‘Yes, madam. Would this white hyacinth do?’ ‘Yes, indeed. It would do excellently well.’ ‘Will you take it, or shall I send it?’ ‘Would you please send it.’ ‘Certainly, madam. Any particular address?’ ‘No. No particular address. Just be sure to send it, and thank you. Good morning!’ ‘Good morning, madam.’♦ Ivor Cutler’s Phonic Poem ↓

A car can go fast on a hill with no brakes and oil on the hump

it cannot stop so it has a spill mum and dad get a cut

see Bill bleed – bleed Bill bleed Kate do not cry –

if you do Ann will be sad to see it and Ted will fret

Phil run to the phone for a nurse to make us well

I see nurse – Nurse, make us well

we are ill from a spill on the road as we took a spin

dad has a cut on his lip – it hit the wheel as he drove fast

mum cut her cheek – see how it shines

Bill is dead – he lost his blood in the crash

Kate, Ann and Ted are sad for Bill – he was their chum

Phil will walk us home along the pavement to our house 29 Redburn Avenue.

⇓ ‘I Think Very Deeply’

I think very deeply I’m a really good thinker People don’t bother me much they can see I’m using my mind

Watch my conclusions oom hoom hoom hoom hoom hoom hoom hoom

◊ ‘GRUTS FOR TEA’ ↓

‘Hello, Billy, teatime! Gruts for tea! – Billy! Billy! Come on, son. Gruts for tea! Fresh gruts!’

‘Oh, I don’t want gruts for tea, Daddy.’

‘What? I went out specially and got them for you.’

‘Aw, but Daddy, we had gruts yesterday.’

‘Look, son, I walked seven miles to the Hi8h Wood to get you gruts. That’s fourteen miles in all, counting the journey back, and you don’t want gruts? I fried them for you. Fried gruts – mm – I fried them in butter.’

‘I don’t want them, Daddy. Daddy, we’ve had gruts for three years now. I’m fed up with gruts. I don’t want them any more. Daddy, can’t we have something else for tea?’

‘Oh, son! Gruts! They’re lovely.’

‘Daddy, I don’t want gruts any more. I hate gruts. I detest them. I have them every day and they’re always fried in buffer. Can’t you think of another way of cooking gruts? There’s hundreds of ways of cooking gruts: boil them or bake them or stew them or braise them – but every day – fried gruts. «Billy, come in for tea. Fried gruts. I’ve walked fourteen miles. Seven miles to the High Wood and back.» Three years of gruts. Look what it’s done to me, Daddy! Come here! Come here into the bedroom and look at ourselves in the mirror, you and me. Now, look at that!’

‘Yes. I see what you mean. Son, let’s not waste these gruts. Tomorrow I’ll go to the High Wood and get something else.’

‘Look, Daddy, you’ve been saying this for three years now. Every day we have this same thing. I take you to the mirror and you say we’ll have something else for tea. What else is there in the High Wood besides gruts?’

‘Well, there’s leaves, bark, grass, and leaves. Gruts are really the best. You must admit it.’

‘Yes, Daddy, I admit it. Gruts are really the best, but I don’t want them. I hate them. I detest them. In fact I’m going’ to take this panful of gruts and throw them out.’

‘Oh, don’t do that! Don’t throw them out for goodness’ sake! You’ll poison the dog!’

∇ A Steady Job ⇓

‘Hello, Sam!´

‘Hello, Daddy. You back?’

‘Yes, son. What in the – where’s your mother?´

‘She’s in the house, somewhere.’

‘Doris! Doris, what the hell’s Sam doing out in the garden buried up to his ankles?´

‘Oh, Bill. I’m so glad you’re home, dear. Three weeks is a long time.?

‘Yes, darling. What’s Sam doing out in the garden?’

‘Bill, I’m broken-hearted. Oh, I’m so glad you’re home. Bill! I don´t know where to begin. The day after you went, some kid at school told Sam he was small. You know how sensitive Sam is. He came home, dug a couple of little holes in the garden, stuck his feet in, stamped the earth down and poured some water over himself and stood there – all night. I didn’t find out till the next morning and I said, «What are you doing, Sam?» and he said, «I’m trying to grow,» and he told me about this fellow at school. I tried to dissuade him but you know Sam. Well, at the end of the week I thought I’d had enough. Despite his protests, I tried to dig him out – and I couldn’t.’

‘What do you mean, dear?’

‘He’d taken root.’

‘Taken root! You’re mad!’

‘No, I’m not. His toes have started to grow and have worked their way down into the earth.’

‘You mean you can’t – get him out? Surely you can find which way his toes have gone and ease them out.’

‘Oh, you don’t understand, Bill. Bill, they’ve – grown all in different directions.’

‘Yes, but it’s not an impossible job.’

‘Bill, Sam is going to have to stay there for ever. Two of his toes have gone under the electric railway at the bottom of the garden and are up in a garden on the other side – lucky it’s someone we know. We’ll never be able to get him out. I spoke to the railway company. They refuse to allow tunnelling underneath their line. They were pretty mad with his toes growing under the line as it is.’

‘Do you mean that Sam is there for ever?’

‘Yes. Yes, Bill. I foolishly let Sam know about this, and he was as pleased as punch; you see – he’s very happy there – growing – in the garden.’

‘But we can’t have that.’

‘Oh, Bill, you know you said that you would let Sam do whatever he wanted to. He’s old enough now to know his own mind. He wants to stand in the garden and grow. I think we ought to let him. Don’t you?’

‘All right then, Doris.’

‘Bill. Go and tell Sam that it’s all right. He’s worried about you.’

‘OK, Doris, I’ll tell him. (Loud) Sam! It’s all right!’

∞ ‘An Unexpected Join’ + ‘A Wooden Tree’ ⇓

‘The earth meets the sky over the hill,’ I was told by a sparrow with a lump on his head.

Hey look there at the back, a wooden tree, isn’t it a pretty one? I called my father to come and look – He cleaned his throat, he started to sing Hey look there at the back, a wooden tree, isn’t it a pretty one? He hollered, ‘Wife!’ – that’s my mother – She took a look, began to below Hey look there at the back, a wooden tree, a pretty one? She called my sister – was in the bath – took a hell of a fright, she lost the sponge and started to moan Hey look, a wooden tree, isn’t it a pretty one? And stared at the back … and stared at the back … and stared at the back … She called my brother, who was right at the back, the flat of the front, to come and look But he wouldn’t come for she hated the words but he knew the tune so he started to hum Hm … hmmm … hmm … hmmm … Along came an artist with paint on his brush – He painted the tree, and now it looks horrible But we keep on singing because we are optimists … Hey – look! * * *♦ ‘My Wee Pet’ ↓ Live 1986

What do I see? A fly and a wasp – A wasp and a mushy well A mushy well in the ground, and the ground sailing ground and drownedCome closer, What do you see?

I see a flea on a fly – A fly and a wasp – A wasp and a mushy well A mushy well in the ground, and the ground sailing ground and drownedJust a minute, I’ll ask my wee chameleon what it sees…

I see an […?] on a flea – A flea on a fly – A fly and a wasp – A triple-decker sandwich How about the mushy well and the ground?

How about the mushy well and the ground?

your article is what i have been looking for a long time. it contains lots of useful information i need. thanks so much and i hope you will keep posting these good information.http://www.silencioso.org

cool, no one will dislike this fantastic blog.http://www.camisaxadrezmasculina.com

articles doesn’t necessarily need too much words to be good, and yours amazing.http://www.callacc.com

I am glad to be one of several visitors on this outstanding site (:, thankyou for posting .

I got what you intend,bookmarked , very nice internet site .

I enjoy the efforts you have put in this, thankyou for all the great posts .

Some really prime blog posts on this site, saved to favorites .